Chapter 10: Experiences of Indigenous Women under Settler Colonialism

If the meta-narrative of Canadian history excluded Indigenous peoples’ stories, it rendered Indigenous women doubly invisible. Indigenous women show up at the peripheries of older settler histories, often exoticized by European observers whose understanding of sexual relationships were peculiarly rigid. Individual women slip in and out of the fur trade records if and when they married and then were deserted by European and Canadian men; they might reappear if they married a successor trader from Montréal or Scotland. A small number loom large. There’s Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Indigenous person in North America to be canonized by the Pope. The campaign to recognize Kateri began in 1680, shortly after her death at about twenty-four years of age, and culminated in sainthood in 2012. Her story—or versions of it—is familiar to the Catholic Indigenous communities and beyond.[1] Another widely-known character is Thanadelthur (ca. 1697 to 1717), held out as a heroic figure in bringing peace to the Dënesųlįné (Chipewyan) and Cree of western Hudson’s Bay. But for all of that, she was dead by the time she was about twenty years old.[2] Konwatsi’tsiaienni (a.k.a. Molly Brant) had a longer career as a diplomat and leader of her people, the Kanien’kehá:ka, and a life that ran from ca. 1736 to 1796. There are other female figures who stand out in the meta-narratives, but not many, and none are so prominent as these three. By the time the Dominion of Canada had taken over responsibility for colonial relations with Indigenous people, Victorian society had ceased to see women as participants in political life: Indigenous women were treated by the Canadians as outsiders in treaty negotiations, and they were excluded from federally-recognized leadership positions within their communities. “Colonial values,” as Carmen Watson points out:

. . . thus began to relegate Indigenous women to apolitical environments, effectively restructuring the socio-political dynamics that had existed pre-contact. Colonizers viewed Indigenous men as the gateway to establishing political, or seemingly political relationships. Women, however, were seen as an impediment to the process, taking up spots that could be occupied by men.[3]

Given this erasure over the course of hundreds of years of colonial history-making, how do we go about recovering and making sense of the histories of Indigenous women?

Women in History

The dominant European narrative of North American history for centuries paid little attention to women’s presence, much less their roles and experiences. Merchants and military leaders from Europe operated within gendered spaces in which women’s roles were very limited; they were wearing those blinkers when they came to North America and, as a consequence, they saw and recorded only what they expected to see. Historian Jan Noel tracked this phenomenon in a study of Haudenosaunee women in the seventeenth-century fur trade. Accustomed to playing a more dynamic and direct role in commerce and community governance than was the case for women in European and settler societies, Haudenosaunee women’s roles were consistently and significantly underestimated by colonial observers who operated from a patriarchal frame of reference.[4] Indeed, the observations of Recollet and Jesuit missionaries on women generally have to be treated carefully insofar as they begin from a particular gendered worldview. By the same token, there was no institution in the British colonies equivalent to the Ursuline Order in New France, an important sisterly organization that placed women in positions of responsibility and relative autonomy. Ursuline accounts of Indigenous women offer a different insight, but they proceed—overwhelmingly—from the same Christian sense of gender as the Jesuit Relations. And yet, ironically, these accounts reach us from a time when the fur trade and conflict were taking men away more regularly from Indigenous communities and thus leaving women in positions of necessarily greater authority, a process that continued through the whole of the fur trade era.

Karen Anderson, a historical sociologist, studied changes in women’s experiences that took place along the St. Lawrence and in Wendake Ehen between 1608 and 1650. From a position of rough social equivalence—one in which men and women had different but complementary and equally valued roles—Montagnais, Naskapi, and Wendat women adopted positions that were significantly more deferential to males. This took place over about thirty years, the period during which the Jesuits were most active. The missionaries ascribed their success in creating this change—in manifesting the kinds of relationship they saw as ideal within Christian societies—to the calamitous social trauma caused by intensified conflict with the Haudenosaunee and exposure to epidemic diseases. Women who resisted conversion were defeated by repeated losses of kin to raids and pestilence. Wendat women in particular stood against any proposed change in their culture that would weaken their pivotal roles as clanmothers and decision-makers, but by 1650 they were submitting en masse to “the domination of their husbands and fathers.”[5] They were more accepting of Jesuitical rule, as well, because they had to seek refuge after the fall of Wendake Ehen.

What did they lose? The right to leave an unsatisfactory marriage, for starters. The Jesuits—who saw marriage as a lifetime commitment—were appalled by the freedom with which Indigenous women abandoned husbands who were regarded as poor providers or partners. They looked at this from the perspective of the Wendat male who, having married a woman for life, found himself abandoned and unable to remarry.[6] To the Jesuit eye, this was a case of women sowing chaos and unhappiness in their community. Over a few decades, the missionaries were able to inculcate in Wendat and Montagnais society a sense that female disobedience was punishable (in this world and in the next) and that female deference—to husband, father, priest, and God—was desirable. Had smallpox not arrived in the 1630s, it is impossible to say whether women’s resistance to these directives (and there was a lot of resistance) would have been more effective.

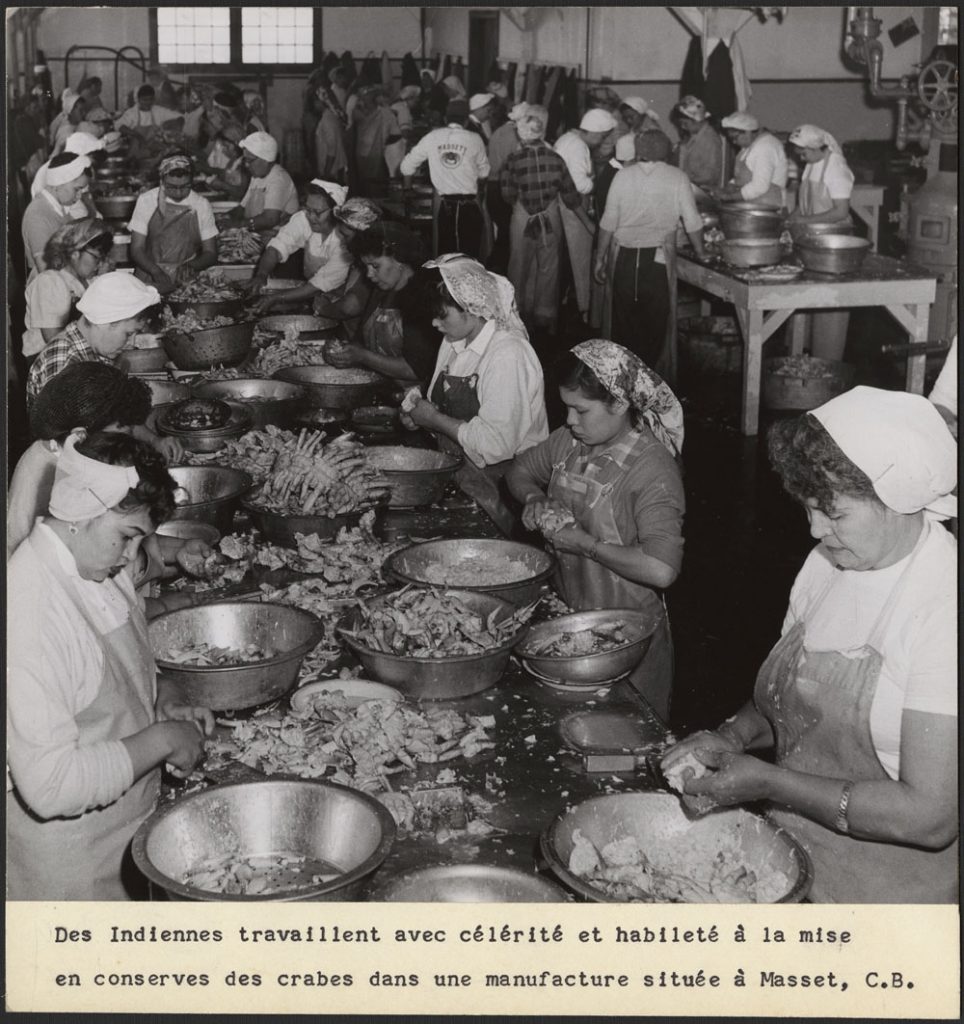

The values espoused by the French missionaries were, in fact, European values, and they would withstand wars and conquest, the arrival of British-American Loyalists and waves of immigrants from Ireland, the transformation of Canada from a pocket of colonies into a trans-continental nation-state, and the inclusion of generations of immigrants from still more remote parts of the world. Settler colonialism, therefore, had a particular colonizing effect on Indigenous women and gendered roles. In some instances it piggybacked on existing gendered roles. This was the case in the fisheries of the Pacific Northwest, wherein men harvested fish while women prepared and preserved the catch; that longstanding practice was brought into canneries in the late nineteenth century in increasingly mechanized spaces that mirrored British, American, and Canadian textile mills in which female labour dominated. Historian Dianne Newell described these processes in a 1993 study:

. . . Indian women, girls, and old people who received wages or piece rates in the fish plants – for scraping and cleaning whole salmon in tubs of cold water; filling cans with salmon; lacquering, weighing, and labeling cans; pickling salmon; making or mending fish nets; and so on – worked in supervised, racially segregated factory settings unlike anything in their aboriginal processing routines. Until the 1940s, Chinese bosses coordinated the efforts of Indian plant workers. Cannery records usually identify Indian women as ‘Kloochmen’ and Indian plant work in general as ‘China labour’ or ‘China crew.’ This set-up differs strikingly from the scenes of salmon-processing witnessed by Alexander Mackenzie [at Nuxalk] in the 1790s.[7]

Women working in canneries from the 1870s to the mid-twentieth century generated the cash needed in an increasingly cash-dependent economy. The purchase and maintenance of boats and nets, along with increased reliance on gasoline engines, reduced self-reliance as competitiveness became tied to the ability to afford better gear.

The labour of women is, in fact, where they show up most in the European record. Nowhere is this truer than in the fur trade.

Métissage

Indigenous communities involved with the fur trade sought and exploited many opportunities to confirm commercial and diplomatic relationships with Euro-Canadians. This was the case when the delegation of Algonquin and Wendat — led by Iroquet and Outchetaguin — visited the French habitation on the St. Lawrence in 1609 with an eye to building a trading and raiding alliance with the French. A century and a half later, as the French were pressing deep into the interior of the continent and the British leaning in heavily from Hudson’s Bay, communities along the Great Lakes and onto the Plains sought stability through alliances of various kinds. Of these, the most consequential was almost certainly marriage.

The work that women invested in the production/processing of pelts and hides put them at the centre of the fur trade relationship. They were able to influence the terms of trade from their community’s side, and a remarkable number of goods obtained from Europeans—copper pots, knives, sewing needles, blankets—either served women’s specific needs or liberated them from the production of equivalent goods. In communities such as those on the Northwest Coast, where potlatching rituals marked clan and household status—something in which women in these societies had a huge stake—whatever women could do to secure more and better goods for potlatching was a worthy project. To that end, women regularly entered into marital relationships with non-Indigenous (or, in some cases, Indigenous but not local) men. Doing so could secure gifts, a supply line of imported goods, better prices, and higher quality. Historian Jean Barman describes one union in the Columbia Valley—involving a daughter of local chieftain (sometimes described as “King”) Comcomly and a Scottish fur trader—that brings together many of these themes:

. . . Ilchee’s relationship with [Pacific Fur Company] partner Duncan McDougall both ensured [Fort] Astoria’s well-being and was profitable from her father’s perspective by virtue of the expected gifts that thereby ensued. According to a contemporary writing in April 1814: “Mr. D. McDougall this afternoon completed the payment for his wife to Comcomly, whose daughter she was: he gave 5 new guns, and 5 blankets, 2 ½ feet wide, which makes 15 guns and 15 blankets, besides a great deal of other property as the total cost of this precious lady.” An Astoria clerk justified the exchange on the grounds that “every thing there went on well owing to Mr. McDougall’s marriage with [Ilchee].” A decade or so later, Ilchee’s sisters or half-sisters Raven and Timmee partnered . . . with HBC officers….[8]

Arrangements of this kind were fluid, more so than was the case in settler society. The partners could sever the marriage (usually a common-law union à la façon du pays) so as to take up with a different partner. It often happened that Euro-Canadian partners departed the West or North for Canada, Britain, or the United States and thus dissolved their marriage. In this way, some women in “fur trade society” came to remarry a series of fur trade men and thus became more deeply woven into the fabric of the industry than any other participants. Along the way, they themselves produced generation after generation of fur traders. For a further example of this, see a brief history of the life and family of Marguerite Waddens.[9]

Fur trade society was comprised of and produced thousands of children whose identities included and bridged, and then evolved beyond, those of their parents. Historian Susan Sleeper-Smith charted the personal and commercial influence of four women who converted to Catholicism and acted as cultural mediators between European society and Indigenous communities. She demonstrates how fur trade society was, for its inhabitants, a network of people, ideas, and loyalties, much more so than just a commercial activity.[10] The complexity of these communities and the speed at which they grew can be glimpsed in an account from a North West Company journal around the start of the nineteenth century. It records twenty-one men, four women, and four children at Red River in 1800, and thirty-seven men, twenty-seven women, and sixty-seven children at Fort Vermillion on the Peace River in 1809. “Henry’s Report of the North West Population, 1805 revealed that the combined total of women and children at individual fur trade posts often outnumbered the men.”[11] In this light, fur trade posts look more like communities and, as they mature, communities in which women’s lives are central to the story.

As a general rule, those individuals whose patrimony included Canadien or Canadian ancestry, and whose maternal line was (mainly) Anishinaabe or Cree, were and are described as Métis; the descendants of British traders associated with the HBC and women from the Dënesųlįné, Cree, and other nations were historically referred to by the British as “halfbreeds” and by historians as “country-born.” Of the two, the Métis more effectively forged their own culture and identity, one that was heavily inflected with Catholicism and an understanding of French and one or several Plains languages. As a community that first sprang up around French fur trade posts and forts in the late seventeenth century, they gradually pursued their own economic order. It was a synthesis of Canadien–style agriculture and Anishinaabe- and Nêhiyawak-style hunting. In this latter respect, they increasingly focused on the bison hunt—for food, the trade in hides, and the production and sale of pemmican. The “country-born” males tended to follow their fathers into the fur trade; some of them were sent to Britain for a conventional European education. Their identity was, thus, less identical. Their sisters tended to stay in North America and became conduits for Plains culture while sometimes marrying young up-and-coming traders in the HBC system. Amelia Connolly Douglas is a good example of how these boundaries are themselves fluid. Her father was Irish-Canadien and her mother, Miyo Nipiy, was Cree. Amelia Connolly was born in 1812 in what is now central Manitoba and spent the entirety of her life in fur trading posts and communities. In 1828 in what is now northern British Columbia, she married a young HBC trader, James Douglas, who reported to her father. She spoke Swampy Cree, some French, English, and possibly several other Indigenous languages. Insofar as any one identity dominated, Amelia was Cree. Should she be considered Métis? Certainly she was of mixed ancestry and came from a Catholic family, but she lacked the crucial connections to the Métis community along the Red River.

By the mid-nineteenth century, settler society was developing a sharper sense of racial boundaries in marriage and association. HBC fur traders (especially the leading traders in the field) increasingly sought non-Indigenous wives. Indigenous women and women of mixed ancestry found themselves marginalized by social sanctions and by new settler-society legal codes that denied them a right to claim inheritances from their settler husbands.

Marrying-Out

The 1876 Indian Act did much to formally strip Indigenous women of their rights and roles. A document conceived and enforced by a patriarchal settler society, one of its goals was to impose and inculcate among Indigenous peoples the values of male land ownership, primogeniture, patrilineality, patrilocality, and female deference.

Under the Act, women gained “Indian status” through their fathers and husbands. This meant that a non-Indigenous woman could acquire status by marrying a man who held status. The flipside of the coin is that any woman with status who married a non-status person would lose her status. This had ramifications for people living on reserves insofar as a non-status woman lost her entitlement to services from Indian Affairs and the reserve bureaucracy.

In 1951, the Indian Act was revised in such a way as to intensify and complicate the implications of marrying out. Now, the children of a status woman who lost her status by marrying a non-status man were also re-categorized as non-status. None of them could vote in band elections or hold office on-reserve, regardless of whether they were male or female. What is more, non-status Indigenous women were, under these circumstances, not merely allowed the franchise; they had to take it.[12] Non-Indigenous women who married status men could gain status before 1951 but they lost it thereafter. Their children sometimes lost their status as well, but not always. The intent was to establish ‘least eligibility’ among Indigenous and status women and their offspring, but the rules were even more slippery in application.

Excerpt from the Indian Act, 1876[13]

CHAP. 18.

An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians. [Assented to 12th April 1876.]

TERMS

3.3 The term “Indian” means

First. Any male person of Indian blood reputed to belong to a particular band;

Secondly. Any child of such person;

Thirdly. Any woman who is or was lawfully married to such person:

(a) Provided that any illegitimate child, unless having shared with the consent of the band in the distribution moneys of such band for a period exceeding two years, may, at any time, be excluded from the membership thereof by the band, if such proceeding be sanctioned by the Superintendent-General:

(b) Provided that any Indian having for five years continuously resided in a foreign country shall with the sanction of the Superintendent-General, cease to be a member thereof and shall not be permitted to become again a member thereof, or of any other band, unless the consent of the band with the approval of the Superintendent-General or his agent, be first had and obtained; but this provision shall not apply to any professional man, mechanic, missionary, teacher or interpreter, while discharging his or her duty as such:

(c) Provided that any Indian woman marrying any other than an Indian or a non- treaty Indian shall cease to be an Indian in any respect within the meaning of this Act, except that she shall be entitled to share equally with the members of the band to which she formerly belonged, in the annual or semi-annual distribution of their annuities, interest moneys and rents; but this income may be commuted to her at any time at ten years’ purchase with the consent of the band:

(d) Provided that any Indian woman marrying an Indian of any other band, or a non- treaty Indian shall cease to be a member of the band to which she formerly belonged, and become a member of the band or irregular band of which her husband is a member:

(e) Provided also that no half-breed in Manitoba who has shared in the distribution of half-breed lands shall be accounted an Indian; and that no half-breed head of a family (except the widow of an Indian, or a half-breed who has already been admitted into treaty), shall, unless under very special circumstances, to be determined by the Superintendent-General or his agent, be accounted an Indian, or entitled to be admitted into any Indian treaty.

From the mid-twentieth century, Indigenous women organized resistance to the Indian Act. In 1985, their efforts were rewarded with reform of some of the Act’s most egregious gender-bias. Bill C-31 addressed the issue of Indigenous women who lost status when they married a non-status male (Indigenous or otherwise), as well as the ramifications this element of the Indian Act had for their offspring. The new legislation restored status to those who had lost it, but the provision—and threat—concerning loss of status was effectively just postponed a generation. Think of it more as a temporary amnesty than a true revision of bad policy.

Listening to Women

A great many of the life studies arising from Indigenous communities in the last twenty years have focused on women. These are, as well, works that are marked by collaborative practices in which the role of the scholarly historian is secondary to that of the knowledge-keeper. Many of these studies are rich with the details of life, rather than the kinds of political landscapes that litter the meta-narrative. Mary John (1913–2004), a Dakelh (a.k.a. Carrier) woman whose twentieth-century life witnessed enormous changes, collaborated with a journalist; her story provides a demonstration of the many acts of resistance that Indigenous women mounted.[14] Many similar partnerships have generated a large enough body of literature that it is now possible to look for commonalities and differences across many nations.

The experiences and activities of Indigenous women in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries indicate both variety and change. They also point to continuity and historic resilience. Women like Mary John worked through initially non-political organizations that emerged in 1968 as the BC Indian Homemakers Association, which had an explicitly political agenda. In doing so, Mary John, her peers, and her successors preserved and advanced a female voice in Indigenous politics.[15]There has been a gradual re-emergence of Indigenous women in positions of authority and influence, perhaps ironically most visibly in the professions and at all levels of Canadian politics. At the same time that we see renewal in female Indigenous power, we witness with revulsion the continuing violence of what is now known by an acronym, MMIWG: missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. A long-running National Inquiry into the apparent disappearance and probable murder of anywhere from one thousand to four thousand individuals delivered its final report in June 2019, declaring violence against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people in Canada as the product of “a race-based genocide.[16] The federal inquest reckons that Indigenous women—who constitute roughly 4 per cent of the female population in Canada—make up 16 per cent of all female homicide victims in the period 1980–2012.[17] The “Highway of Tears” in northern British Columbia has been one focus of the MMIWG Inquiry, as has the rate of female homicides in Winnipeg. While these tragedies have unfolded over decades—and continue to unfold—the rate of incarceration of Indigenous women remains badly skewed. In Alberta, roughly half the women in the prison system are Indigenous; nationally, they are 36 per cent of the female federal prison population.[18] The residential schools may be closed and subject to scrutiny by historians, but penal institutions—many of which owe their beginnings to the federal government’s annexation of the Prairies—continue to elude the same kind of scrutiny.

Conclusion

As a political organization, the Indian Homemakers’ Associations provide us with a segue into the next chapter. Women historically and consistently played leading roles in Indigenous communities’ efforts to thrive and to confront colonialism. The twentieth century would see experimentation with a wide variety of tactics and organizations whose aim was to mitigate and reverse the worst effects of colonialism.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

Anderson, Karen. Chain Her by One Foot: The Subjugation of Native Women in Seventeenth-Century New France. London & New York: Routledge: 1991.

Bailey, Norma, dir. Women in the Shadows. 1991. Montreal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/women_in_the_shadows/

Barman, Jean. “Aboriginal Women on the Streets of Victoria: Rethinking Transgressive Sexuality during the Colonial Encounter.” In Contact Zones: Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada’s Colonial Past, edited by Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale, 205–27. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005.

Carter, Sarah, and Patricia McCormack, eds. Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands. Edmonton: Athabasca University, 2011.

Charlie, Rose. “Indian Homemakers’ Association of British Columbia.” Indigenous Foundations. Accessed February 13, 2019. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_homemakers_association/

Erickson, Lesley. “Constructed and Contested Truths: Aboriginal Suicide, Law, and Colonialism in the Canadian West(s), 1823–1927.” Canadian Historical Review 86, no. 4 (December 2005): 596–618.

McCallum, Mary Jane Logan. Indigenous Women, Work and History 1940–1980. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014.

Raibmon, Paige. “The Practice of Everyday Colonialism: Indigenous Women at Work in the Hop Fields and Tourist Industry of Puget Sound.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 3, no. 3 (2006): 23–56.

Paul, Elsie. Written as I Remember It: Teachings (Ɂəms tɑɁɑw) from the Life of a Sliammon Elder. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014.

Roy, Susan, and Ruth Taylor. “‘We Were Real Skookum Women’: The shíshálh Economy and the Logging Industry on the Pacific Northwest Coast.” In Indigenous Women and Work: From Labor to Activism, edited by Carol Williams, 104–19. Urbana, Chicago, & Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Sangster, Joan. “Criminalizing the Colonized: Ontario Native Women Confront the Criminal Justice System, 1920–60.” Canadian Historical Review 80, no.1 (March 1999): 32–60.

Silman, Janet (as told to). Enough is Enough: Aboriginal Women Speak Out. Toronto: Women’s Press, 1987.

Thorpe, Jocelyn. “Indian Residential Schools: An Environmental and Gender History.” NICHE: Network in Canadian History & Environment/Nouvelle initiative Canadienne en histoire de l’environment, April 27, 2016. http://niche-canada.org/2016/04/27/indian-residential-schools-an-environmental-and-gender-history/

Trimble, Sabina. “A Different Kind of Listening: Recent Work on Indigenous Life History in British Columbia.” Canadian Historical Review 97, no. 3 (September 2016): 426–34.

Welsh, Christine, dir. Finding Dawn. 2006. Montreal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/finding_dawn/

- Allan Greer’s video on Saint Kateri is listed in Chapter 9. Also, see his book, Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). A more recent Indigenous feminist and environmentalist take on the subject is Michelle M. Jacob’s Indian Pilgrims: Indigenous Journeys of Activism and Healing with Saint Kateri Tekakwitha (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2016). ↵

- The familiar narrative of Thanadelthur is unpacked in Patricia A. McCormack, “The Many Faces of Thanadelthur: Documents, Stories, and Images,” in Reading Beyond Words: Contexts for Native History, 2nd ed. (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2003), 329–64. ↵

- Carmen Julia Zarifeh Watson, “Unsettling Kin: Fractured Generations, Indigenous Feminism, and the Politics of Nationhood,” unpublished B. A. Honours graduating essay, University of British Columbia, 2018, p. 8. ↵

- Jan Noel, “Fertile with Fine Talk.” ↵

- Karen Anderson, Chain Her by One Foot: The Subjugation of Native Women in Seventeenth-Century New France (London & New York: Routledge, 1991), 52. ↵

- Ibid., 76–77. ↵

- Dianne Newell, Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 53. ↵

- Jean Barman, French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous Women in the Making of the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 131. ↵

- John Douglas Belshaw, “Identity Crisis,” in Canadian History: Pre-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2015), section 13.7. ↵

- Susan Sleeper Smith, “Women, Kin, and Catholicism: New Perspectives on the Fur Trade,” Ethnohistory 47, no. 2 (2000): 423–52. ↵

- Racette, “Nimble Fingers and Strong Backs,” 150. ↵

- Lianne C. Leddy, “Indigenous Women and the Franchise,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, April 7, 2016, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indigenous-women-and-the-franchise. ↵

- Indian Act, chap. 18, § 3-3 (1876). ↵

- Bridget Moran, Sai-k’uz Ts’eke: Stoney Creek Woman, the Story of Mary John (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1988, 1997). ↵

- See Sarah Nickel, “‘I Am Not a Women's Libber Although Sometimes I Sound Like One’: Indigenous Feminism and Politicized Motherhood,” American Indian Quarterly 41, no. 4 (Fall 2017): 2. ↵

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report, https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/ ↵

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs, “Background on the Inquiry,” Government of Canada, accessed November 14, 2018, www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. ↵

- Emma McIntosh and Alex McKeen, “Overrepresentation of Indigenous People in Canada’s Prisons Persists amid Drop in Overall Incarceration,” The Star (Toronto, ON), June 19, 2018, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2018/06/19/overrepresentation-of-indigenous-people-in-canadas-prisons-persists-amid-drop-in-overall-incarceration.html; Geraldine Malone, “Why Indigenous Women are Canada’s Fastest Growing Prison Population,” Vice Magazine, February 2, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/5gj8vb/why-indigenous-women-are-canadas-fastest-growing-prison-population. ↵