Chapter 9: Cultural Genocide—Belief Systems, Residential Schools, Potlatch Laws, “Sixties Scoop”

As the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples points out, negotiations between colonial elites set the stage for the Confederation project through the 1860s:

At no time, however, were First Nations included in the discussion, nor were they consulted about their concerns. Neither was their future position in the federation given any public acknowledgement or discussion. Nevertheless, the broad outlines of a new constitutional relationship, at least with the First Nations, were determined unilaterally. The first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, soon informed Parliament that it would be Canada’s goal “to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion.”[1]

“Assimilation” in this context meant, in part, religious conversion and an end to many Indigenous cultural practices.

Indigenous Peoples and Christianity

It is difficult to know with absolute certainty what Indigenous peoples thought of early European efforts at indoctrination. The sources to which we might turn are overwhelmingly filtered accounts transmitted by the missionaries themselves. What we can say for certain is that seventeenth-century representatives of Catholicism had neither the power nor numbers to force Christianity on anyone, nor was it the case that all Indigenous peoples were entirely unreceptive.

From 1615–29, the Innu, Algonquian, and Wendat studied the spiritual message of the Recollets. In less than fifteen years, it was clear that the first of the “black robes” had failed to persuade more than a handful of people into converting. Tolerating and cooperating with the Recollets was broadly acceptable among Indigenous communities, but indulging all of their views was not. Besides which, the Recollets were primarily concerned with preserving Christian behaviour and attitudes among the French traders. This was not the approach taken by the Jesuits.

The Society of Jesus owed much to military traditions. Its members embraced hardship and martyrdom in ways that other Catholic orders simply did not. Wendat communities found this, at least, interesting. What’s more, the Jesuits were directly linked to the commercial interests of the French colony. This enabled the missionaries to blur the lines between commerce and conversion. Their strategy was to appeal to whole communities rather than to individuals. They opened an all-boy seminary near Québec in 1636, with the goal of converting these young men and returning them to Wendake Ehen as a vanguard of Christianity. They also established a base in Wendake Ehen, where the Jesuits closely observed the spiritual practices of the Wendat and attempted to meet the Wendat on their own spiritual ground. Jesuit accounts of the Wendat Feast of the Dead show genuine awe and respect, noting both the richness of the multi-day ritual and also the ways in which it bound together the communities of Wendake Ehen. From the Jesuit perspective, as historian Erik Seeman observes, there were analogies to be drawn with Catholic ideas:

Both groups adhered to religions that focused on the mysteries of death and the afterlife. Both believed that a dead person’s soul traveled to the afterlife. Both believed that careful corpse preparation and elaborate mortuary rituals helped ensure the safe transit of the soul to the supernatural realm. And both believed in the power of human bones.[2]

Historians are divided as to the place of Christianity in Wendake Ehen. Bruce Trigger saw Wendat interest in conversion as perhaps a disingenuous bluff to gain access to more trade goods (especially and increasingly guns). Seeman doesn’t entirely disagree, but he qualifies this equation by pointing to the spiritual investment Wendat people made in material goods. The fact that perfectly good copper pots were regularly interred with the bones of the dead indicates that the lines between material and spiritual were oftentimes very thin indeed. Victoria Jackson examined the experience of three Jesuit-schooled Wendat boys—Satouta, Teouatiron, and Andehoua—and concluded that the children served successfully as cultural diplomats, less so as conduits for Christianity.[3] The jury, in short, is still out.

As smallpox tore up Wendake Ehen in the 1630s, burial and reburial rituals became larger, and spiritual exhaustion seems to have set in. The Jesuits offered both a salutary message of spiritual reunion in the afterlife and the problematic practice of deathbed baptisms. Since Wendat physicians were simultaneously spiritual practitioners, traumatized Wendat households looked to the Jesuits to occupy a similar position and understood baptism to be a kind of curing ritual. But deathbed baptisms by definition almost always end in a death, and that compromised the missionaries’ reputation. The devastation of the smallpox epidemics, in which approximately half of Wendake Ehen’s population died, was followed a decade later by a renewal in Haudenosaunee attacks. Together these developments contributed to a crisis in Wendat belief systems. It also drove a wedge between “Christian” and “traditionalist” Wendat, many of the latter calling for the removal of the missionaries and a return to older Wendat belief systems. Relinquishing the Jesuits, however, meant jeopardizing the supply of weapons and other metal goods, much of which were needed in the battle against the Haudenosaunee. In the end, it was the Five Nations raiders who, in 1649, relieved Wendake Ehen of the Jesuits—by means of torture and eventual execution.

The Wendat encounter with the Jesuit (and even Recollet) black robes reveals a few important patterns. First, the Wendat showed a genuine interest in European spiritual knowledge; the Wendat were neither passive recipients of cultural imperialism, nor were they immovable in their beliefs. The seventeenth-century Wendat had the curiosity and the intellectual wherewithal to selectively engage another belief system and selectively and incrementally adopt and adapt elements. Also, European willingness to study Indigenous cultures and to become functional in, in this case, the Wendat language indicates that the missionaries’ goal was spiritual transformation and not cultural assimilation. The 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal People set the scene thus:

To the Jesuits their mission was akin to a war against satanic forces and was intended to reap a rich harvest of souls. In their battle, the missionaries were armed with formidable intellectual weapons, since all had studied and taught a variety of academic subjects for at least six years in prestigious French colleges. What ensued was a remarkably sophisticated philosophical discourse, in which some of the most educated men of Europe engaged in long arguments deep in the Canadian wilderness with shamans and village elders equally adept at debating metaphysical issues from their own cultural perspective.[4]

What the Royal Commission fails to mention—although it is as good as implied here—is that European concepts of “educated” imply credentials from formal institutions. Indigenous systems of “education” included reflection and metaphysics as well. The absence of fine universities did not disadvantage Indigenous debaters.

Power relations would change in subsequent centuries and in different settings, European attitudes toward Indigenous beliefs would become increasingly contemptuous, and the saving of souls (as the missionaries understood it) would play less a role than cultural assimilation. Some of this transition in purpose and attitudes can be seen at Port Simpson on BC’s Northwest Coast in the late nineteenth century. There, a Methodist mission was actively pursued by the Ts’msyan community, whose leadership “sought missionaries’ practical skills and newcomer knowledge as a means of helping their people to accommodate to the dramatic changes occurring all around them.”[5] A home—a kind of refuge—was established for Indigenous girls (some of them orphans), and it quickly transitioned into a place of incarceration in which their behaviours were more heavily monitored, policed, and challenged. Removal from family and community increasingly became the strategy pursued by the Methodist missionary family.[6] This approach was consistent with the tactics of the colonial state after 1867.

The State Steps In

Responsibility for “Indian Affairs” passed in 1860 from Britain to the colonies. In 1867, the individual colonies-cum-provinces relinquished that brief to the new federal government in Ottawa. Subsequent joiners—BC in 1871 and PEI in 1873—would follow suit. Article 13 of BC’s Terms of Union spells this out in a way that was both self-congratulatory and deceptive:

The charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit, shall be assumed by the Dominion Government and a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government shall be continued by the Dominion Government after the Union.[7]

However “liberal” the colonial policy had been under the pre-Confederation regimes of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, it had taken a seriously illiberal turn under Joseph Trutch, a surveyor who became chief commissioner of land and works and a member of the Legislative Council. Reserves were hacked back, land grants ended, and the whole concept of “aboriginal title” denied. Trutch was at the negotiating table in Ottawa on behalf of the new province, and his goal was to ensure that Ottawa would be “as liberal” but no more liberal than his own illiberal regime. He needn’t have worried. Ottawa’s influence in the lives of Indigenous people and communities involved, from 1867 on, a heavy hand.

Aboriginal-Newcomer Relations since Confederation (CC BY 4.0)[8]

Jennifer Pettit, Mount Royal University

Section 91, Subsection 24 of the British North America Act made the federal government responsible for all matters related to Indigenous peoples, and made First Nations peoples into wards of the Federal Government. The portfolio of Indian Affairs was placed under the guidance of the Secretary of State and, despite some early failures, much of the earlier legislation and policies were maintained including the civilization plan, treaties, and the reserve system. Additionally, some new legislation was passed including the Enfranchisement Act (1869), which made enfranchisement compulsory in some cases (such as when an Indigenous woman married a non-Indigenous man), promoted individual land ownership, and granted the government the power to impose an elective band council system of governance. As had been the case in the past, these changes were made largely to benefit non-Indigenous society without consultation with First Nations peoples. The government was concerned with the territorial growth of Canada; acquiring land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in the West; creating the new provinces of Manitoba, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island; and creating an Indian Lands Branch in the new Department of the Interior in 1873.

The most significant piece of legislation in this period was the passage of the Indian Act of 1876.[9] Consisting of 100 sections, the Indian Act consolidated earlier legislation and addressed a wide variety of areas concerning lands, status, and governance. At the core of the Act was the reinforcement of the policy of aggressive assimilation and colonization. This Act, among other things, defined who was and was not an “Indian” according to the government, described band election procedures, defined a band and reserve, and discussed the management of resources including timber and band monies. Invasive and paternalistic, the Indian Act ignored the diversity among Indigenous groups in Canada, and treated Indigenous peoples as children who required management. Made into wards of the state, Indigenous peoples were no longer autonomous according to the government. As was the case in the past, central to the Indian Act and new policies was the plan to separate Indigenous peoples from their land through a system of treaty-making and reserves, and increased farming instruction and schools for Indigenous children. This plan was particularly important in Western Canada to clear the way for settlers who were central to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s National Policy, one part of which was the settlement of the West through immigration. However, first, the government had to extinguish Indigenous title through a series of treaties signed in the early and mid-1870s.

Given the changes brought about by the numbered treaties and the expanding importance of the Indian Affairs portfolio, in 1880, the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior was turned into a separate department called the Department of Indian Affairs, although the Minister of the Interior continued to act as Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs and oversaw the new department. There would be much to focus on, including strengthening the civilization program through the promotion of farming instruction and schools.

As we’ve already seen, the Indian Act (1876) aimed to transform Indigenous peoples. Efforts to eradicate behaviours and beliefs that were regarded as profoundly different from or inferior to those of mainstream European-Christians were undertaken at governmental levels. The banning of the potlatch, for example, was motivated by a sense that it was wasteful, that it disinclined participants from working steadily for a living, and that it was an offence to the Christian/settler values of thrift, hard work, private property, and the accumulation of savings and wealth. One Methodist missionary to the Stó:lō spoke for most of his Christianizing peers when he said that “Of the many evils of heathenism, with the exception of witchcraft, the potlatch is the worst, and one of the most difficult to root out.”[10] Dances that accompanied potlatch ceremonies—many of which were generations-old stories and involved life lessons—appeared, in the eyes of some Christian outsiders, as invocations of evil spirits. All of these factors—along with a growing Protestant sense of the individual’s importance as a soul to be saved, as an economic actor, and as a private citizen—combined to produce hostility toward ceremonies in what is now British Columbia and an outright ban on the potlatch in 1884. Some of these arguments were also made against the Plains cultures’ “Sun Dance,” and it too was banned in 1885.

The literature focuses on these aspects of culture, but it tends to ignore governance: it is as though the early post-contact impression held by Europeans that Indigenous societies lacked any form of government haunts historical writings. The Indian Act, however, was clear on this score: existing systems for selecting community leaders would be replaced by regular elections overseen by the Indian agent. Hereditary systems were to be dismantled and/or ignored; “Indian chief” became an actual job and, by the 1920s, it came with a special badge and hat, and sometimes a uniform. In response to these settler society policies, Indigenous peoples were, of course, inclined to disbelief. Why would anyone attempt to shut down rituals, celebrations, and institutions that glued whole societies together and made them economically viable? Why indeed.

Indigenous people and communities responded with protest and, probably more importantly, quiet defiance of these restrictions. As far as was possible, injunctions against community self-determination in government were ignored. In the case of the Mi’kmaq, fifty years of Canadian interference witnessed resistance, rejection, work-arounds, and exploitation of the new system when it served a purpose.[11] Farther west, the potlatch and Sun Dance (and other practices) continued, though increasingly with great discretion. The Indian agent, the RCMP, and the Provincial Police could not be everywhere at once. In 1922, however, the potlatch laws came down hard at the north end of Vancouver Island. ‘Namgis chief Pal’nakwala Wakas (more widely known as Dan Cranmer) and his peers, along with dozens of guests, held what may have been the largest potlatch in a century at ‘Mimkwamlis in Kwakwaka’wakw territory. An alert and zealous Indian agent ensured that arrests took place; jail sentences of as much as three months were ordered for nearly two dozen women and men who were shipped off to a Vancouver-area penitentiary. What is more, a great mass of privately-owned cultural belongings—masks, regalia, carved figures—were seized by the BC Provincial Police and sold off to non-Indigenous collectors or shipped east to museums in Toronto, DC, and London.[12]

These events sent a chill through many Northwest Coast communities; settler society hostility toward the potlatch and the Sun Dance got worse before getting better. As the Summary Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission observes:

In 1942, John House, the principal of the Anglican school in Gleichen, Alberta, became involved in a campaign to have two Blackfoot chiefs deposed, in part because of their support for traditional dance ceremonies. In 1947, Roman Catholic official J. O. Plourde told a federal parliamentary committee that since Canada was a Christian nation that was committed to having “all its citizens belonging to one or other of the Christian churches,” he could see no reason why the residential schools “should foster aboriginal beliefs.” United Church official George Dorey told the same committee that he questioned whether there was such a thing as “native religion.”[13]

It was not until the 1950s that the laws criminalizing the potlatch and Sun Dance were relaxed sufficiently to encourage an open return to the traditional observances. It is worth pausing at this point to reflect on the fact that Indigenous people at this time were, in some cases, incarcerated in the Canadian penal system because they very simply refused to relinquish beliefs and values.[14]

These colonialist initiatives were intended, in the words of the deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, in 1920 “to prepare [Indigenous people] for a higher civilization.” That “higher civilization” was, of course, Canadian settler society. This was an age of efficiency experts in industry and business; their ideals shine through in Scott’s words: “Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question.”[15] The most aggressive, long-standing, and now notorious measure taken to achieve assimilationist goals was the residential schools.

Residential Schools

Why residential schools? One thing to keep in mind is that public schooling was, in the late nineteenth century, still something of a recent innovation in colonial society. Child labour laws in the 1870s were unevenly defined and poorly enforced; consequently, attendance at settler schools other than those for the elite was marked by high levels of truancy and absenteeism. It was rare for a child in Canada to complete more than a few years of formal education. Institutionalized education was, however, seen as a means of addressing social problems, specifically hordes of young unsupervised children in the Dominion’s growing cities. In short, schools were viewed by many not as a tool with which to enlighten generations to come but as a means of controlling and changing the inmates. That at least partly explains why the federal government regarded schools as the right instrument to use in transforming Indigenous children. But why residential? John A. Macdonald, speaking in the House of Commons in 1883, explains:

When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the [Indian Affairs] Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.[16]

Jennifer Pettit describes the origins of the residential school system and how it followed on the heels of agricultural schools promised in numbered treaties. Pettit points out how the original stated goals of the system were visibly failing by the 1920s. It took another thirty years before substantial changes in the formal schooling system took place. In the box that follows, John Belshaw describes the arc of the residential school story from the 1970s on and also surveys the Sixties Scoop and other interventions by the state in the lives of Indigenous children.

From Agricultural Training to Residential School (CC BY 4.0)[17]

Jennifer Pettit, Department of Humanities, Mount Royal University

By the time the numbered treaties and the reserve system were created, Indigenous peoples in what is now Western Canada faced dire conditions. Many communities were ravaged by diseases such as smallpox, and devastated by the whisky trade. The bison, on which they relied, was almost extinct.[18] The Canadian government once again decided that the solution was model farms to accompany a policy of peasant farming through which Indigenous families were to receive “2 acres and a cow” — and through which they were not encouraged to utilize any labour-saving machinery. The government felt this would ensure Indigenous peoples would be converted to sedentary farmers, but would not be so successful that they would compete with the new settlers moving west. Not surprisingly, the plan failed. Government bureaucrats at the time blamed the supposed “lazy” nature of First Nations peoples. Historian Sarah Carter has since proven that Indigenous peoples were interested in farming, but that the government’s policies and practices undermined reserve agriculture.[19] More important to the government was a new system of schools for Indigenous children.

Though they had weak results in the early schools in central Canada, the Federal Government was optimistic that expanding schools into the Prairies made sense, hopeful that the Indigenous peoples there could also be “civilized and Christianized.”[20] Starving and destitute, some Indigenous peoples also hoped the schools would teach their children the skills necessary to adapt to changing conditions and, ideally, to learn a trade that would make them self-supporting. What remained to be determined though was what kind of education system would best serve the Indigenous peoples living in the West. To help answer that question in 1879, the government enlisted Nicholas Flood Davin (1840-1901), a Regina newspaper editor and the M.P. for Assiniboia West, to study the American system of industrial schools for Indigenous peoples. Notably, as was the pattern in government dealings with Indigenous peoples, Davin did not consult First Nations. He concluded that industrial schools in which children learned a trade and which were similar to those in the United States would be appropriate and useful in the West, despite disappointing results in similar schools in Central Canada. Davin also suggested that the Canadian government forge alliances with the churches to manage the schools.[21] These “industrial” schools were costly, however, and as a result, a parallel system of day and boarding schools was also created. Boarding schools were similar to the industrial schools, but were typically smaller with a much reduced focus on trades instruction. The first of the industrial schools — the Qu’Appelle Industrial School and the Battleford Industrial School located in the future province of Saskatchewan, and the St. Joseph’s School (also known as the High River or Dunbow school) southwest of Calgary — opened in the 1880s. These schools would lay the groundwork for a system of schools that would eventually spread across the Prairies and into British Columbia and the North.

By the time the last school closed in 1996, over 130 would have operated and over 150,000 Indigenous children would have been forced to attend what would ultimately be deemed tools of cultural genocide.[22] Indigenous children were taken from their homes, separated from their communities and families, and were forbidden to speak their languages or practice their culture. Students were poorly fed; subjected to medical experiments; forced to undertake manual labour; and were subjected to physical, sexual, and mental or spiritual abuse.[23] The legacy of this appalling treatment is still being felt in Indigenous communities today.[24]

To ensure the schools “succeeded,” the government enacted a number of measures including compulsory attendance in 1894 (and reinforced in further legislation in 1920). However, the parents of Indigenous students were not passive participants in the plans of church and state to “civilize” their children, and many did whatever they could to prevent their children from attending these schools and to demonstrate their displeasure. Parents were angered that their children were being abused and that they were taken so far away from the reserves. Parents were also upset that students were alienated from their culture, were forced to work long hours, were not properly cared for, and could not find employment after graduation. This opposition took place, however, in a power relationship in which Aboriginal peoples were unable to bring about real change. Thus, their opposition had only a limited effect. What did sway the administrators was rising costs.

Originally thought to be a quick and relatively inexpensive way to deal with what administrators deemed the “Indian Problem,” the schools had evolved into a costly and complicated system that was not producing significant results. As a consequence, Duncan Campbell Scott (1862-1947), who was appointed to the position of Superintendent of Indian Education in 1909, changed the professed goal of schools for Indigenous peoples from integration to segregation (in the words of Scott: “for civilized life in his own environment”). In 1923 officials merged the industrial and boarding schools to create a new category of schools known as “residential schools.”[25] Scott, though, still very much believed in a policy in which Indigenous peoples should be obliterated as a distinct community. In 1920 he made this now famous statement: “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone.… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question . . . ”[26]

In the box that follows, John Belshaw describes the arc of the residential school story from the 1970s on and also surveys the Sixties Scoop and other interventions by the state in the lives of Indigenous children.

The Legacy of the Residential Schools (CC BY 4.0)[27]

John Douglas Belshaw, Thompson Rivers University.

The goals of the Residential School system were explicitly assimilationist. The program existed precisely to replace Indigenous economic practices with those of the mainstream colonial economy, substitute English and French for indigenous languages, erase indigenous belief systems with some kind of Christianity, and interrupt the transmission of social practices (including fundamental familial relationships) by capturing children and keeping them away from their parents, siblings, and other relations. This needs to be underlined: there was nothing accidental about the way the residential schools turned out; these were clearly stated goals and tactics.

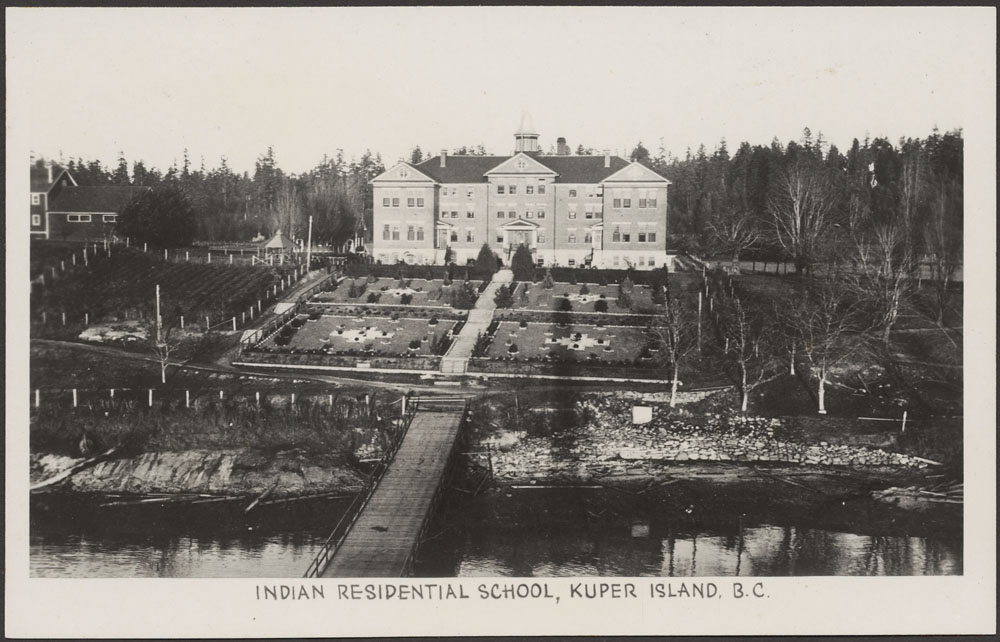

At the peak in the 1930s, there were roughly 80 residential schools in Canada. They were in seven of the nine provinces; there were none in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, nor in the Dominion (later, the province) of Newfoundland. Most of the schools were located far from urban centres. As institutions go, the large brick or stone structures were universally imposing. At Kamloops (Tk’emlúps), for example, the Indian Residential School, opened in 1893, was the largest brick structure in the Thompson Valleys and, indeed, between the Lower Mainland and the CPR hotels of the Rocky Mountain national parks. A brick-works was established to enable its construction. On Kuper Island, at Alert Bay, and in town after town across the Prairies, two- and three-storey buildings were erected to enable the warehousing and transformation of generations of Native children.

The involvement of the nation’s Christian churches from the outset, was viewed by officials as a good way to transmit Euro-Canadian cultural values, morals, and discipline. It was, as well, cheap, because missionary groups would effectively work for free. Over half of the schools were run by the Catholic Church, most of the rest by the Anglicans, and the remainder by the United Church and the Presbyterians. Conditions varied from place to place, but few were adequately funded; by the second quarter of the twentieth century, child labour was an essential component of the residential school business model. Through most of their history, the general practice at residential schools was to provide only half-day schooling; the rest of the day was dedicated to labour in the fields and workshops and mopping the floors, all in an effort to keep the children busy and reduce operating costs. The schooling the students received was light on the humanities, lighter still on sciences and math, and heavy on religion and theology. Generally speaking, girls were taught domestic skills like cooking and sewing, while boys were taught basic agricultural skills and some crafts.

Children were housed in dormitory rooms. Rows of beds allowed for little privacy. Boys and girls were separated and kept separate: stories abound of brothers and sisters who were allowed no contact despite being kept in the same building. Showers and baths were spartan. Meals were Dickensian, and children suffered from malnutrition. Complaints of cold facilities are sustained by a terrible record of mortalities from illnesses, including tuberculosis (which claimed as many as 60% of the student population). Every residential school has its own sad little graveyard, and some of them aren’t that little. As Mary-Ellen Kelm has pointed out, some schools kept their mortality statistics low by shipping fatally ill children home to their families, which consequently inflated mortality rates on reserves. Kelm also has noted that the transformation of Indigenous diets to Euro-Canadian foods was part of an attempt to colonize not only the mind but the Indigenous body as well.[28]

Whether Indigenous leaders found the concept of the industrial and then residential schools helpful to their people or not, the reality fell very far short. Parents often resisted sending their children away, and it was one of the functions of the RCMP and units like the BC Provincial Police to assist the clergy with annual roundups of students. It wasn’t until the late 1950s that the educational curriculum improved and children were allowed to visit with family over the holidays. The record suggests that a great many parents discovered that their child had died at school only when the summer holidays began.

Beginning in the 1950s, Indigenous children were permitted to attend public schools for the first time, and as day-students. Family connections were rebuilt, but the residential schools remained in place for most of the youngest Indigenous children in the country. In 1969 the D.I.A. took over the operation of the schools from the churches, which coincided with the Red Paper and the rise of Indigenous political organizations. However, this is not to say that there was unanimity among Indigenous peoples as to what should happen next. Gradually, the responsibility for the schools’ operations shifted to local band councils. By 1986 all of the schools were in the hands of Indigenous managers, and many had been closed down entirely.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as plans advanced to end the schools program, the consequences of a century of residential schools were everywhere visible. Traumatized children became traumatized adults and they were systematically pathologized by settler professionals. Social workers drawn from the colonizing society were sent to reserves — often with RCMP and other police supports — to “rescue” children from dysfunctional environments in which colonialism itself was heavily implicated. In the decade after 1955, as a study by Christopher Walmsley points out, “Aboriginal children in the care of the Province of British Columbia jumped from less than 1% to 34.2%, and this pattern was repeated in other parts of Canada during the same time.”[29] Just as residential schools were being closed, the Federal Government’s monopoly over the management of Indigenous communities on-reserve began to fray, and provincial involvement increased:

The principal response of provincial child welfare authorities during the 1960s was the apprehension and removal of Aboriginal children from their families and communities. Known as the “sixties scoop,” social workers explained their actions by arguing that they were in the best interests of the children.[30]

Citing poverty, health concerns, and even malnutrition, the secular authorities perpetuated the alienation of children from their communities that had begun under the missionaries and residential schools. Indigenous children in care were placed with non-Indigenous families, and some were exported to the United States. In almost every case, the link between child and ancestral culture was severed. Whether in care or in residential schools, the same outcomes prevailed: practices – especially, but not exclusively, those censured by the anti-potlatch and sun dance laws – were inadequately passed from one generation to the next; the skills taught at woefully underfunded schools prepared students for nineteenth century field labour but not twentieth century factories or offices, let alone professions. Substance abuse on reserves, particularly alcohol, was extensive as people self-medicated to deal with everything from a personal sense of diminished self-worth to cultural alienation to systemic poverty and – from generation to generation – the loss of children. Whereas the reserve system and pass system were designed to keep Indigenous people physically in check, the residential school system and the intervention of colonialist social workers and police authorities were intended to keep them culturally in check.

The enormous educational, social, and moral failures of the residential school system are now widely known. The system contained a single ineluctable contradiction: it proceeded from an explicitly racist assumption that indigenous cultures were inferior and proceeded to strip away those features with an eye to assimilating native people into “mainstream” society, but neglected to address the inherent racist and discriminatory perspectives of Euro-Canadians who would not hire, marry, work with, drink with, study with, lend money to, extend the franchise to, or vote for Indigenous people, regardless of whether they were “schooled” or not. “Assimilation” was entirely about change, and not about inclusion. It could hardly be otherwise under the circumstances.

It is reckoned that 150,000 children passed through the system from the end of the nineteenth century to the mid-1980s. Some of the structures are still standing: St. Eugene near Cranbrook has been converted into a luxury resort/casino and now generates revenue for the Ktunaxa First Nation; the Kamloops Indian Residential School houses offices and a museum for the highly entrepreneurial Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. Other schools are no more: the Penelakut/Kuper Island school was demolished in the 1980s, as was St. Michael’s at Alert Bay very recently – in both cases, the prohibitive costs of repair and rehabilitation were a factor, as was an unwillingness to tolerate the gloomy presence of the buildings any longer.

There were, clearly, systemic weaknesses and shortcomings to the residential schools. Underfunding alone would have produced many of the negative outcomes that have been so widely documented. Tales of physical and sexual abuse operate at a different level. The principle Christian denominations were viewed by Euro-Canadian society as moral guardians; as a result, Canadians found it difficult to accept tales of abuse. Evidence began to accumulate and patterns began to emerge in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1990 the leader of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Phil Fontaine (b. 1944), publicly disclosed the sexual abuse he suffered as a child in residential schools, along with his reckoning that every boy in his class was similarly mistreated. This disclosure led to others and, in 1991, a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was convened. Seven years later, the Minister of Indian Affairs issued a formal apology to victims of sexual abuse in the schools, and a multi-million dollar fund for healing was established. While this process uncovered some very grim tales, it did not speak to the psychological, physical (in addition to sexual), and emotional abuse experienced routinely in the schools. Priests and nuns alike, as well as secular workers at the schools, were named, some charged, and some convicted of a wide range of sadistic practices. One survivor of St. Anne’s Residential School at Fort Albany, Ontario, shall have the last word. She went on record to describe the kind of abuse meted out by one nun:

I remember being in the dining room having a meal. I got sick and threw up on the floor. Sister Mary Immaculate [Anna Wesley] slapped me many times and made me eat my own vomit. So I did, I ate all of it. And then I threw up again … Sister Mary Immaculate slapped me and told me again to eat my vomit. …I was sick for a few days after that.[31]

Residential schools were not the only institutions attended by Indigenous children. Day schools run by the DIA (rather than the clergy) replaced many residential schools, and pupils numbered nearly eighteen thousand by 1955. The option to attend settler society’s public schools became another more attractive option for a growing number of teens. Although these changes did little to reverse the tide of cultural colonization—assimilation and integration are, ultimately, different tactics with the same goal—they improved educational outcomes for some. And simply by dint of not being held within the walls of residential schools, Indigenous teens were protected from some of the worst abuses in the church-run facilities. The option of attending a public school was, of course, only available to those Indigenous youths living close to settler communities. In the meantime, residential schools remained open.

In 1969, the clergy relinquished control of the residential schools to the DIA, and the system was incrementally shut down. Over the course of little more than a century, there were twenty-eight residential schools in British Columbia alone. Of these, three were operated by the Anglican Church, five by the Methodists, three by the Presbyterians, and the majority—sixteen—by the Catholic Church. Thirteen were still in operation in 1970, and the last—the now-state-run St. Mary’s at Mission, BC—closed in 1985. The last residential school in Canada—Gordon Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan—remained in operation until 1996. The process of winding down the system, in other words, was not pursued with great alacrity.

The Métis and Inuit Experience

Things unfolded rather differently in Métis and Inuit communities. There were substantial variations from coast to coast to coast. Different mainstream Christian and evangelical denominations were involved, and they conducted themselves differently with respect to the students, their parents, and even with the DIA and Ottawa.

Successive federal governments had little patience for the Métis after the events of 1869–70, and less still after 1885. There were few treaties signed with the Métis[32]—despite their clear wish to establish a treaty relationship—and so the Métis regularly fell outside the framework of colonial oversight. When it came to education, this meant that the federal government tried to offload onto the provinces the responsibility and cost for schooling Métis children. Overwhelmingly Catholic, Métis families looked to orders like the Oblates to provide their children with schooling. In some communities, such as Mission in the Fraser Valley, the only Catholic school was the residential school. Bit by bit, Ottawa denied Métis children access to these facilities; it did the same, on the whole, to children who were ancestrally mixed Indigenous and Euro-Canadian—described at the time as “halfbreeds”—but who did not share the cultural inheritance of the Métis.[33] As a consequence, separate residential schools were established by provincial and church authorities to address the demand for schooling from the Métis and “halfbreed” communities. There is an irony here in that many of the educators in this system were themselves Métis. As the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reminds us, Louis Riel was teaching at a boarding school for Métis boys in Montana on the eve of the 1885 rebellion, and his sister Sara taught at the Île-à-la-Crosse boarding school for Métis students.[34] This occurred because nineteenth-century Métis communities largely embraced Western notions of institutional education, within and without the Church system.

As we shall see in Chapter 10, the question of “status” under the Indian Act had particular and intentional impacts on Indigenous women and their children. Loss of status—through marriage to a non-Indigenous man—cost any offspring their status and thus their right to an education paid for by Ottawa. Despite many exceptions, the general pattern was one of “least eligibility”: reducing the cost of running federally-funded schools by removing Métis/“halfbreed” children. This was increasingly the case in the 1930s as the economy collapsed and federal funding became more lean. In 1937, the federal government declared that it never had an obligation to educate Métis children, and blocked any further enrolments.[35]

The education of Métis children at Île-à-la-Crosse and in a few other locations was in many respects hardly different from that of Indigenous children elsewhere. Conditions were poor and their treatment was bad. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, however, makes the point that we know far less about the history of Métis children in residential or public schools than we do of the experiences of status Indian students. The situation of Inuit children was also exceptional.

Ottawa paid little attention to Inuit peoples’ needs before the middle of the twentieth century. The Klondike Gold Rush presented an opportunity and necessity for treaties north of 60, but it wasn’t until the Second World War and the building of the Alaska Highway that Ottawa renewed its interest in the region. In the 1950s, changes in technology and infrastructure increased the possibility of Canadians accessing and extracting natural resources in the sub-Arctic and Arctic. The Diefenbaker government’s “Roads to Resources Program” of 1957–63 was one expression of this new outlook. As the Cold War took off in the 1950s, too, there were growing concerns about expressions of Canadian sovereignty in the North: an official Canadian presence in Arctic communities thus served a variety of economic and political purposes.

Suddenly, then, Inuit children found themselves in newly-established residential schools funded by Ottawa. These built on and advanced the efforts of denominational schools, such as the Catholic Immaculate Conception Residential School established at Aklavik in 1925 and the neighbouring Anglican All Saints Indian and Eskimo Residential School (opened in 1936). The model used by the federal government in the North, however, was distinct. It included day schools and a close connection with public schools.[36] There were few non-Aboriginal students in the public schools so, in effect, they were all institutions catering overwhelmingly to Indigenous and Inuit children and youths. The dormitory or hostel schools were large, and they had an unusual impact on population distribution in the North. In the South, it was typically the case that children were removed from their families’ reserves and homes and transported some distance to the residential schools; in the North, the hostels were constructed at nodes that met Ottawa’s needs first, and then Inuit families migrated to those sites and established substantial towns as a result. Inuit dependence on Ottawa’s Family Allowance system was accelerating in these years, as was the campaign against tuberculosis. These two developments further tied Inuit people to the emergent school communities.

The mission-run schools were gradually replaced by federally-funded institutions, although the clergy remained a critical piece of the education system. Bizarre circumstances arose in small communities. Inuvik provides a good example: there, the Anglicans’ Stringer Hall and the rather more notorious Grollier Hall run by the Catholic Church stood side by side, with roughly 200 pupils in each. They shared grounds and other facilities, but the pupils were otherwise kept separate. There were even cases of siblings within view of one another but separated denominationally and allowed little or no contact. In northern Québec, beginning in 1960, there were both federally- and provincially-funded residential schools for Inuit children; Inuit families were in a position to choose to which school(s) they would send their children. The federal system wound down in the early 1970s, and in 1975 the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement led to both the Inuit and the Innu (a.k.a. northern Québec Cree) establishing their own autonomous school boards.

As a final note on the northern experience, Labrador stands apart in several ways. There were Moravian missions in Labrador from 1771, and mission schools for Inuit children were an early feature. In the late nineteenth century, evangelical British organizations arrived and largely ignored the Inuit population until the 1920s. As a result, neither St. John’s in the period before Newfoundland’s union with Canada, nor Ottawa after 1949, took much of a direct interest in these residential/dormitory schools. Regardless, conditions were much the same: speaking Inuktitut was forbidden on pain of punishment; siblings were separated; food was both alien to the Inuit children and insufficient to nourish them properly; abuses occurred.[37]

Historians and the Residential Schools

Historians have played an important role in developing public awareness of the residential school system, the individual schools, and the conditions therein. Landmark publications that spurred settler-society attention and Indigenous community responses include Celia Haig-Brown’s 1988 book, Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School. Some historians, like Jim Miller in his important article, “Owen Glendower, Hotspur, and Canadian Indian Policy,” show how Indigenous peoples acted to use or resist coercive efforts at assimilation.[38] This position—and similar, contemporary arguments made by Tina Loo, Doug Cole, and Ira Chaikin in the 1990s—have been criticized by other historians for apparently minimizing the negative effects of colonialism. “Resilience” and “agency” in this context is read by some as a “colonialist alibi.” To which Miller, Loo, Cole and Chaikin replied, their colleagues were “motivated by a ‘sense of contrition . . . a wish to do penance by “redressing past injustices.”’”[39] Historians have, as a whole, conceded that Indigenous agency in the face of institutions like residential schools existed, was resourceful, and mattered, but that—in the longer haul—it faced tremendous challenges.

Other historians have focused on fully documenting the extent of abuses and deplorable conditions in church- and government-run facilities. All are in agreement with BC historian Jean Barman that the quality of education provided was substantially—and in most cases purposefully—so far below what was available in settler society schools as to render Indigenous students uncompetitive and badly under-prepared for work in and engagement with modern society.[40] These studies are both informed by and reflect the kind of resistance Miller documented. And in some measure they set the stage for the wider public discussion in the 1980s and ’90s of the residential schools debacle, leading to two public apologies by the federal government.

Having said that, two points need to be underlined: first, historical studies make it clear that settler society representatives and organizations involved in these projects knew what they were doing and what conditions were like at the time, and they chose to endorse, accept grudgingly, or turn a blind eye to those conditions; a few protested but without result. Second, whatever the contribution of scholars to this discussion, it pales before the courageous testimony of “survivors” of residential schools.

Conclusion

Much effort has been spent by colonial society on changing Indigenous people’s metaphysical, material, and social knowledge—indeed, everything we conventionally bundle together as “culture”—and most of that has been aimed at children. Like Noel Annance, many Indigenous childhoods in mission villages, in the care of early French missionaries, in schools, in foster care, and even in penal institutions, have involved captivity. Of course, children—if things go well enough—become adults, and so it is the case that behind every adult there is a child. Which is to say, the experience of “captivity” of this kind is carried forward through adulthood. Some relationships between settler societies and Indigenous societies, however, focus specifically on one category of adult: women. The next chapter considers the histories of Indigenous women with an eye to the gendering of settler-Indigenous relations.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

Abel, Kerry. “Prophets, Priests, and Preachers.” In Drum Songs: Glimpses of Dene History, 113–44. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993. (The second edition contains similar material.)

Barman, Jean. Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance, 1792–1869. Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016. See esp. pp. 39–66.

Bradford, Tolly, and Chelsea Horton, eds. Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016. See esp. pp. 1–20.

Carson, James Taylor. “Brébeuf Was Never Martyred: Reimagining the Life and Death of Canada’s First Saint.” Canadian Historical Review 97, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 222–43.

Dussault, René, Georges Erasmus, Paul L. A. H. Chartrand, J. Peter Meekison, Viola Robinson, Mary Sillett, and Bertha Wilson. Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples: Volume 1—Looking Forward, Looking Back. Ottawa: 1996. See esp. pp. 309–94.

Elbourne, Elizabeth. “Managing Alliance, Negotiating Christianity: Haudenosaunee Uses of Anglicanism in Northeastern North America.” In Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada, edited by Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton, 38–60. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016.

Greer, Allan. “Dr. Allan Greer Question 1 – Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.” TRU, Open Learning. October 28, 2015. Video, 7:07. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GCtjs9pBr18

Haig-Brown, Celia. “The ‘Friends’ of Nahnebahwequa.” In With Good Intentions: Euro-Canadian and Aboriginal Relations in Colonial Canada, edited by Celia Haig-Brown and David A. Nock, 132–57. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006.

Haig-Brown, Celia. Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1988. Rev. ed. 2006.

Hare, Jan, and Jean Barman. “Good Intentions Gone Awry: From Protection to Confinement in Emma Crosby’s Home for Aboriginal Girls.” In With Good Intentions: Euro-Canadian and Aboriginal Relations in Colonial Canada, edited by Celia Haig-Brown and David A. Nock, 179–98. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006.

Ignace, Ron, and Marianne Ignace. Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws: Yeri7 Re Stsq’ey’s-Kucw. Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017. See esp. pp. 404–24.

Kurjata, Andrew. “Four Deaths, No Action: ‘Notorious’ B.C. Residential School Explored in New Project.” CBC, January 4, 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/lejac-residential-school-four-boys-runaways-death-1.4473885

Marker, Michael. “Borders and the Borderless Coast Salish: Decolonising Historiographies of Indigenous Schooling.” History of Education 44, no. 4 (2015): 480–502.

McCallum, Mary Jane Logan. “‘I Would Like the Girls at Home’: Domestic Labour and the Age of Discharge at Canadian Indian Residential Schools.” In Colonization and Domestic Service: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Victoria Haskins and Claire Lowry, 191–209. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Miller, J. R. Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts its History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

Morgan, Cecilia. “Dr. Cecilia Morgan Question 3 – Methodism and the Anishinaabe.” TRU, Open Learning. October 28, 2015. Video, 3:01. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEklD7BY6Jc

Podruchny, Carolyn, and Kathryn Magee Labelle. “Jean de Brébeuf and the Wendat Voices of Seventeenth-Century New France.” Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Réforme 34, no. 1–2 (Fall 2011–Winter 2012): 97–126.

Raibmon, Paige. “‘A New Understanding of Things Indian’: George Raley’s Negotiation of the Residential School Experience.” BC Studies 110 (Summer 1996): 69–96.

Raptis, Helen, with members of the Tsimshian Nation. What We Learned: Two Generations Reflect on Tsimshian Education and the Day Schools. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016. See esp. pp. 27-102.

“Residential Schools.” Eugenics Archives. Accessed October 3, 2019. http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/institutions/residential.

Smith, Donald B. “Jones, Peter.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_8E.html.

Stevenson, Allyson. “Selling the Sixties Scoop: Saskatchewan’s Adopt Indian and Métis Project.” Active History, October 19, 2017. http://activehistory.ca/2017/10/selling-the-sixties-scoop-saskatchewans-adopt-indian-and-metis-project/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. They Came for the Children: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools. Ottawa: Library and Archives of Canada, 2012. See esp. pp. 21–53.

Walmsley, Chris. Protecting Aboriginal Children. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005. See esp. pp. 8–30.

- René Dussault et al., Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (Ottawa: 1996), 165. ↵

- Erik Seeman, The Huron-Wendat Feast of the Dead: Indian-European Encounters in Early North America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), 2. ↵

- Victoria Jackson, “Silent Diplomacy: Wendat Boys’ ‘Adoptions’ at the Jesuit Seminary, 1636–1642,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, New Series, 27, no. 1 (2016): 139–168. ↵

- Dussault et al., Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 103–4. ↵

- Jan Hare and Jean Barman, Good Intentions Gone Awry: Emma Crosby and the Methodist Mission on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006), xix. ↵

- At the same time, the missionaries found their status challenged by a Ts’msyan leadership disappointed in the benefits of their arrangement: the Ts’msyan subsequently recruited Salvation Army missionaries to act as their culture guides. Hare and Barman, Good Intentions, xxii. ↵

- Senate of Canada, “Article 13 of Schedule: Address of the Senate of Canada to the Queen,” in British Columbia Terms of Union (UK: Court at Windsor, 16 May 1871), accessed December 10, 2018, https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/constitution/lawreg-loireg/p1t42.html. ↵

- Jennifer Pettit, “Aboriginal-Newcomer Relations since Confederation.” Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. ↵

- See John Leslie, The Historical Development of the Indian Act (Ottawa, ON: Treaties and Historical Research Centre, 1978). ↵

- Thomas Crosby, Among the An-Ko-me-nums, 106, quoted in Smith, “11.6 Living with Treaties.” ↵

- Martha Elizabeth Wells, No Need of a Chief for this Band: The Maritime Mi’kmaq and Federal Electoral Legislation, 1899–1951 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010). ↵

- Two studies by the late Doug Cole remain important resources in this field: Douglas Cole and Ira Chakin, An Iron Hand Upon the People: The Law Against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1990); Douglas Cole, Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995). ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honouring the Truth, 5–6. ↵

- The repatriation of Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch gear began in 1973. While much remains outside of Canada and in the hands of private collectors, the material that was recovered led to a renewal in potlatching in Kwakwaka’wakw communities. This is described in Harry Assu with Joy Inglis, Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989), 104–21. ↵

- Quoted in Dussault et al., Royal Commission, 168–9. See also the website of the U’mista Cultural Centre, accessed February 12, 2019. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honouring the Truth, 2. ↵

- Jennifer Pettit, “From Agricultural Training to Residential School,” in John Douglas Belshaw, Canadian History: Post-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 11.7. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- See James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains. ↵

- See Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests. ↵

- See J. R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1996) and John Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986 (Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 1999). ↵

- Nicholas Flood Davin, Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds, March 14, 1879, Library and Archives Canada, Record Group 10, Vol. 6001, File 1-1-1. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honouring the Truth, 3. ↵

- Ian Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942–1952,” Histoire sociale/Social History 46, no. 91 (2013): 615–642. ↵

- Canada, Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Vol. 5: Renewal: A Twenty-Year Commitment. In For Seven Generations: An Information Legacy of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, (Ottawa: Libraxus, 1997), CD-ROM. ↵

- Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1986). ↵

- Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, testimony before the Special Committee of the House of Commons examining the Indian Act amendments of 1920, Library and Archives Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, volume 7, pp. 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3). ↵

- John Douglas Belshaw, “Residential Schools,” in Canadian History: Post-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 11.11. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- Mary-Ellen Kelm, Colonizing Bodies: Aboriginal Health and Healing in British Columbia, 1900–50 (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1998). ↵

- Christopher Walmsley, Protecting Aboriginal Children (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2005), 2. ↵

- Ibid., 13–15. ↵

- Jesse Staniforth, “Cover Up of Residential School Crimes a National Shame,” The Star (Toronto, ON), August 25, 2015, http://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2015/08/25/cover-up-of-residential-school-crimes-a-national-shame.html. ↵

- The most obvious exception is Treaty 8, which was negotiated in 1899. ↵

- The term “halfbreeds” was applied to children of European/Euro-Canadian and Indigenous ancestry, often regardless of whether they might self-identify as Métis. Sometimes officials made the distinction; sometimes not. We use the term “halfbreed” here with care, so as to indicate populations of mixed ancestry while recognizing the particular cultural qualities of the Métis community. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Canada’s Residential Schools: The Métis Experience (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University, 2015), 8–9. ↵

- Ibid., 26–28. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Canada’s Residential Schools: The Inuit and Northern Experience (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University, 2015), 8–9. ↵

- Ibid., 190–4. ↵

- J. R. Miller, “Owen Glendower, Hotspur, and Canadian Indian Policy,” Ethnohistory 37, no. 4 (Autumn 1990): 386–415. ↵

- See Alan C. Cairns, “Aboriginal Research in Troubled Times,” in Roots of Entanglement: Essays in the History of Native-newcomer Relations, eds. Myra Rutherdale, Kerry M. Abel, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 414–6. ↵

- Jean Barman, “Schooled for Inequality: The education of British Columbia Aboriginal Children,” in Children, Teachers and Schools in the History of British Columbia, 2nd ed., eds. Jean Barman and Mona Gleason (Edmonton: Brush Education, 2003), 55–80. ↵