Chapter 7: Settler Colonialism & Treaty Peoples

This chapter considers the ways in which elements of Indigenous peoples’ relationships with an emergent imperial/nation state evolved from 1763 to the early twentieth century. It focuses on the versions of the future expressed by hopeful Indigenous negotiators under often very difficult circumstances. The treaty era on the Plains and resistance to the settler regime are considered more fully in Chapter 8.

There are a number of intellectual developments to keep in mind as we survey this period. First, there is the rising impact of racialized perspectives. As indicated earlier, binary categories of “Indians” and “whites” began to take hold during the late eighteenth-century wars in the Ohio Valley and in the years from 1800 to 1814 around the Great Lakes. These views would only intensify in the decades that followed, alleviated in settler society briefly by the rise of humanism at mid-century. And although Indigenous societies would differentiate between the motives and tactics of Canadians, British-Canadian fur traders, Americans, and others, they themselves would commonly use “Indians” in a way that indicates a consciousness of categorization and experience. The term simultaneously holds up a mirror to white, settler society.

Second, there is the rise of science and technology as a factor in the lives of Indigenous peoples and settler societies to consider. The early stages of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism in settler societies fractured the centuries-old relationship between two largely rural peoples. The collapse of the beaver and otter fur trade, the advance of the bison robe and hide trade (some of it, ironically, in support of the industrial drive-belt sector and the mass production of fine “bone” china) with the consequent precipitous decline of bison stocks, the invention of repeating rifles, and the arrival of intercontinental railways all set the stage for increased pressures on Indigenous peoples in the West in particular. Changes in the social priorities of settler colonies in these years include the rise of formal schooling and state institutions like courts, prisons, asylums, and governments, alongside a revival of the missionary impulse. The unfolding of some of these forces may be detected very long ago, but they are definitely evident after the War of 1812.

Marginalization: Life During Peacetime

The Americans and the British signed the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814. Let’s pause for a moment to consider how the context of Indigenous life had changed, and how it would look in the year that followed.

The British Crown had cast a large net across much of the continent. It was able to exclude other European nations from the great expanse of Rupert’s Land (where the Hudson’s Bay Company operated a trading monopoly and increasingly acted like a little government). Farther east, the British claimed almost all of the Wabanaki territory and had carved it into five separate administrative units: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Prince Edward Island, and Lower Canada, where Abenaki communities clustered along the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. The remainder of the Wabanaki peoples could be found in the state of Maine in the United States—a country that had only recently been at war with Britain and British North America. Another branch of Mi’kmaq remained in yet another British colonial possession, Newfoundland. That colony, at least, did not have its own administrative system as yet. On the mainland, to be succinct, the Wabanaki after 1763 had the British on all sides of them; in 1784 they had the British on three sides, the Americans on the fourth, and thirty-six thousand Loyalists pouring into their midst. By 1815, the Mi’kmaq and Wuastukwiuk were badly outnumbered and scrambling to retain what they could of their ancestral lands.

Colonial officials did little to address the increasing desperation of Mi’kmaq and Wuastukwiuk communities. Access to traditional foraging areas on the coast was being lost; settlers squatted on what little arable land the Wabanaki could secure; transitioning to European-style agriculture (which, in many cases, Mi’kmaq sought to pursue) presented challenges; settlers competed for wildlife; and the logging industry exploded in the first half of the nineteenth century, resulting in rapid deforestation and erosion along the major river systems of the region. In so many ways, the Wabanaki world was in distress. The Mi’kmaq and Wuastukwiuk faced starvation (a worsening situation in the early 1830s) and, given the apparent fate of the Beothuk (pronounced extinct in 1829), they had cause to be concerned for their longer-term prospects. While Halifax and Fredericton were aware of the extent of the problem facing Indigenous peoples, the two colonial governments had neither the capacity nor the inclination to do anything about it.

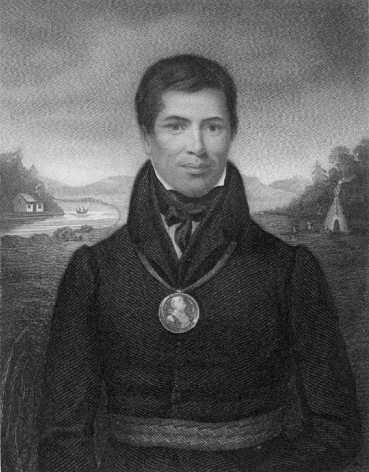

In 1841–42, conditions in Nova Scotia appeared to change, catalyzed by Mi’kmaq diplomatic actions. Paussamigh Pemmeenauweet (1755–1843) was recognized in 1814 by the settler regime in Halifax as “chief” of the “Micmac Indians” of Nova Scotia.[1] For years he presented petitions to the colonial assembly and to touring Catholic clergy and bishops, calling for aid to the Mi’kmaq people. These were not ignored, nor were they truly acted upon. In 1841 Paussamigh Pemmeenauweet addressed a new petition to Queen Victoria (at that time only twenty-two years old and on the throne for a mere four years). The response was direction to the settler administration to establish an Indian commissioner under the colony’s own Indian Act (1842).

Letter to Queen Victoria from Louis-Benjamin Peminuit Paul, received in the Colonial Office, London, 25 January 1841[2]

To the Queen

Madame: I am Paussamigh Pemmeenauweet…and am called by the White Man Louis-Benjamin Pominout. I am the Chief of my People the Micmac Tribe of Indians in your Province of Nova Scotia and I was recognized and declared to be the Chief by our good friend Sir John Cope Sherbrooke in the White Man’s fashion Twenty Five Years ago; I have yet the Paper which he gave me.

Sorry to hear that the king is dead. I am glad to hear that we have a good Queen whose Father I saw in this country. He loved the Indians.

I cannot cross the great Lake to talk to you for my Canoe is too small, and I am old and weak. I cannot look upon you for my eyes not see so far. You cannot hear my voice across the Great Waters. I therefore send this Wampum and Paper talk to tell the Queen I am in trouble. My people are in trouble. I have seen upwards of a Thousand Moons. When I was young I had plenty: now I am old, poor and sickly too. My people are poor. No Hunting Grounds — No Beaver — No Otter — no nothing. Indians poor — poor for ever. No Store — no Chest — no Clothes. All these Woods once ours. Our Fathers possessed them all. Now we cannot cut a Tree to warm our Wigwam in Winter unless the White Man please. The Micmacs now receive no presents, but one small Blanket for a whole family. The Governor is a good man but he cannot help us now. We look to you the Queen. The White Wampum tell that we hope in you. Pity your poor Indians in Nova Scotia.

White Man has taken all that was ours. He has plenty of everything here. But we are told that the White Man has sent to you for more. No wonder that I should speak for myself and my people.

The man that takes this over the great Water will tell you what we want to be done for us. Let us not perish. Your Indian Children love you, and will fight for you against all your enemies.

My Head and my Heart shall go to One above for you.

Pausauhmigh Pemmeenauweet, Chief of the Micmac Tribe of Indians in Nova Scotia. His mark +.

The first settler to occupy the position of Commissioner was Joseph Howe, a journalist and prominent reformer who was far more interested in high-level politics in Halifax than Indigenous affairs. Howe faced requests to restrain squatters, conduct proper surveys of Mi’kmaq lands, and assist their transition to new economic activities. In reply, he assessed the conditions facing the Mi’kmaq and provided a pessimistic prognosis for their future. Howe concluded that Mi’kmaq numbers were falling so quickly that they would join the Beothuk as an extinct people in forty years or so. With fewer than fifteen hundred left in Nova Scotia, their circumstances were indeed perilous. Howe’s successors did not change course: even assimilationist strategies (education, agricultural training) were regarded as throwing good money after bad.

The situation in early nineteenth-century Upper Canada was similar in that settler encroachment was quickly cutting into Indigenous lands. But there was more space in the region, and access to traditional resources was slower to disappear. The threat of squatters was, however, very much on the mind of Anishinaabe representatives in the aftermath of the War of 1812. They agreed to relinquish certain lands in exchange for annuities, an arrangement that echoes the tribute-gifts of the days of New France (which, to be clear, were still within living memory). This approach appealed to the Indigenous participants because it served as a kind of guaranteed income in perpetuity; it worked well for the colonists because it freed up lands relatively quickly. This is, in all likelihood, how the idea of annuities became embedded in Canadian treaty agreements in the decades to follow.[3]

By the 1830s, the situation was worsening for the Anishinaabe. Militarily, they were themselves weakened and unable to stand up to settler incursions. More than that, their ancestral allies across the whole Great Lakes region were now dispersed by the Americans. Increasingly, the Anishinaabe were an Indigenous island encircled by settler societies. In addition to petitions that resembled what the Mi’kmaq were trying in the Maritimes, the Anishinaabe increasingly made use of their connections with the Methodist Church.

The Upper Canadian wheat boom of the early and mid-nineteenth centuries increased demand for farm land and increased the wealth that could be earned from land sales, and this created still further pressure, pushing some Anishinaabeg into rocky northern quarters where the opportunities to take up farming were less viable. Whether bought out or shipped out by well-meaning or predatory colonial administrators, the effects were the same: the majority of Anishinaabeg moved from their position as the dominant peoples and force within Southern Ontario on the eve of the War of 1812 to a remote and increasingly impoverished and missionized cluster of reserve communities by 1860.

These conditions set the stage for Victorian-era treaty negotiations between Indigenous peoples and Canada.

Treaties from 1763 to 1921

There are some general themes and specific consequences of the treaty process.

From an Indigenous perspective, a common complaint has been that there is an inherent and significant difference between “the Crown” and “the government.” Among the Anishinaabe and Anihšināpē in particular (but not exclusively), the symbolic significance of signing an agreement with Queen Victoria—who was represented in the negotiations as a matriarch—was far more powerful than any agreement between business partners or even official diplomats could ever be. Niitsitapi belief that a “covenant” is an agreement involving three parties, one of whom is a spiritual figure or deity, further complicates the meanings of treaties. The question of joint occupation of lands was no less complicated. In every case that has been carefully documented—and this covers at the very least every treaty east of the Rockies and in the Yukon—it is clear that Indigenous negotiators did not intend to concede land absolutely and in perpetuity. The use of land was to be shared, and Indigenous access to traditional resources would in no way be impeded. Shared use is significantly different, too, from shared ownership. It is difficult to imagine, based on oral tradition and written evidence arising from the treaty processes, that Indigenous signatories foresaw the carving up of their lands into freehold lots that could be bought, sold, and owned forever by anyone, let alone outsiders.

Instead, common Indigenous goals in seeking treaties include erecting reasonable barriers against waves of settlers and/or resource-seeking industries. Other common provisions were food, medical support, education, and agricultural instruction, all of which reflects fear of lethal epidemics like smallpox and measles, and of starvation in the wake of declining food resources (especially bison). These priorities also point to a desire to better understand the colonial world and to become better equipped to face it.

From a Canadian perspective, we need to consider first the constitutional landscape. From 1763 to 1840, all responsibility for negotiations and treaties resided with the British Crown and was handled by direct representatives of the British government. At the end of this period, the British government handed responsibility to the government of the Province of Canada, but only for its territory at that time (that is, the heartland of Ontario and Québec). On the West Coast at mid-century to 1871, the British remained directly responsible for treaty negotiation, but effectively left it in the hands of the colonial governments of Vancouver Island and British Columbia (which the Crown did not support with resources). In 1867, Ottawa’s responsibility for treaty-making (and -keeping) extended to the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Two years later, Britain divested the HBC of Rupert’s Land and transferred responsibility over the region to the new Canadian government, conditional on Ottawa negotiating treaties with the peoples of the region. This federal responsibility implicitly extended thereafter to newly added, created, and expanded provinces: Manitoba (1870), British Columbia (1871), Prince Edward Island (1873), Alberta and Saskatchewan (1905), northern extensions of Ontario and Québec (from 1877 to 1912), Manitoba’s northern expansion (1912), and the admission of Newfoundland (1949). It is important to note that while Canada eventually (over a period of not less than fifty years) addressed its obligation to Britain as regards Indigenous lands and treaties in what was Rupert’s Land, it chose to understand British Columbia’s situation as exceptional. The Peace District in the province’s northeast was part of Rupert’s Land, so Ottawa negotiated treaties there. As for the rest of the province, Ottawa saw it as exempt from the provisions of the 1763 Royal Proclamation and opted to pursue no treaties beyond the fourteen Vancouver Island treaties signed by Governor James Douglas in the 1850s.

Had Canada modeled its government on the United Kingdom and produced a unitary state, at least all would know where final responsibility for “Indian Affairs” resides. But it is and has been since 1867 a federal state. Under the constitution—from the BNA Act of 1867 to the current Constitution Act (1982)—provinces have responsibility for most resource sectors, apart from fisheries.[4] So, while ultimate responsibility for relations with Indigenous peoples resides with “the Crown,” in practical terms it has become the responsibility of Ottawa; at the same time, there is inevitable jurisdictional overlap, duplication, and conflict between the provinces and Ottawa that impacts the business of honouring the terms of treaties.

As Canada claimed and annexed more land in the West, the prospect of settler intrusions grew larger. The arrival of surveyors—who were sent west to map out land for settlers and, most aggressively, for railway routes—spurred Indigenous interest in negotiations with the Canadians. The collapse of the fur trade also drove interest in treaties. This was coupled to the growing belief among Indigenous peoples that a transition to farming or ranching might be the best strategy. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, some western leaders, including Isapo-muxika (a.k.a. Crowfoot), took up Canadian invitations to visit the emerging city of Winnipeg, the capital in Ottawa, and what the Canadians regarded as “model” reserves in Ontario and Québec. Impressed by what they saw, they advocated for the addition of schools and teachers’ salaries in treaties.

In the section that follows, Professor Keith Smith surveys the evolution of the Treaty relationship and introduces us to the implications of the Indian Act of 1876.

Living with Treaties (CC BY 4.0)[5]

Keith Smith, Departments of History and First Nations Studies, Vancouver Island University

Not unlike communities in Europe or elsewhere, the Indigenous peoples of North America confirmed access to resource sites, facilitated trade, resolved conflicts, settled alliances, and navigated the mass of other relations with their neighbours by negotiating agreements. When European newcomers found their way into Indigenous territories, they realized it was in their interest, and often necessary for their survival, to learn Indigenous treaty protocols and to fit themselves into Indigenous commercial networks. After these initial encounters, over time, treaty making changed in intent and content, but whether for military alliance, access to land and resources, or for some other reason, all of those involved understood that only agreements of this sort could protect the often divergent strategic, cultural, and economic interests of the treaty partners.[6]

The significance of treaty making to the newcomers is evident in Britain’s Royal Proclamation (1763) that, in part, committed it and then Canada to gain the consent of Indigenous Nations before settling in their territories. This commitment led to several treaties on Canada’s West Coast, and in what became Ontario and southern Manitoba prior to 1867. Soon after Confederation, the treaty process continued with the negotiation of the so-called “numbered treaties,” the first seven of which were concluded between 1871 and 1877 and covered the southern region between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains. For its part, Canada was primarily concerned with the acquisition of land and the fulfillment of its promise to British Columbia for a transcontinental railway. First Nations, on the other hand, were generally interested in protecting their territories and resources from incursion, while at the same time ensuring their cultural survival and independence. For them, these treaties were peace treaties. As Piikani (Peigan) elder Cecile Many Guns (aka: Grassy Water) confirmed almost a century after the treaties, the intent was that there would be “no more fighting between anyone, everybody will be friends . . . Everybody will be in peace.”[7]

From the perspective of the newcomers, the transfer of land stood above all other policy considerations, and the numbered treaties were presented as successful mechanisms by both politicians of the day and many later historians. However, it is becoming increasingly recognized that rather than representing everything that was agreed to, the written treaties are much more reflective of Canada’s goals and Euro-Canadian interpretations of treaty-making, and much less representative of the objectives of First Nations and of Indigenous understandings of treaty processes. Many of the arrangements that were presented and agreed to orally during treaty negotiations are absent or minimized in the text of the numbered treaties.[8] The actual meaning of these treaties remains in dispute among historians and in the courts.

Reserves

As a central provision of the numbered treaties, and where there were no treaties as Federal Government policy initiatives, isolated enclaves called Indian reserves were created to accommodate Indigenous people. The reserve system, as it developed in the mid to late 19th century, was meant as a temporary measure only, providing closed sites where missionaries and agents of the state could indoctrinate Indigenous populations in the economic, political, religious, and social conduct acceptable to settler Canada. Reserves offered residents refuge of sort from the various forms of discrimination they faced in the outside world, but to policy makers and church officials, they were laboratories of reform where residents could be observed and judged and where “Indian-ness” could be instructed, legislated, or coerced out of Indigenous people.[9] On these fragments of ancestral territories, Indigenous residents held the right to occupancy only. Ownership and title remained in the hands of Canada.

Since non-Indigenous lawmakers took for themselves, even in treaty areas, absolute authority to decide who would own land, reserve size depended largely on local settler demand. Even in areas covered by the numbered treaties, reserve size was calculated differentially on the basis of between 160 and 640 acres per family of five, while in British Columbia, for example, 10 acres per family was established as the standard. These inequities, and the smaller average reserve land base in Canada compared to the United States, were recognized and challenged by Indigenous political movements such as the Allied Tribes of British Columbia during the First World War and Interwar period, but they have largely remained to the present day.[10]

Regardless of the original size of reserves, even these small tracts remaining to Indigenous people were often under threat. While the Federal Government restricted the ability of reserve communities to manage the lands they lived on, Canadian officials were more than willing to alienate reserve lands themselves to meet settler demands for mineral, forest, or agricultural lands; for the construction of transportation routes or military sites; or for a myriad of other purposes. While often, though not always, Indigenous agreement of a sort was sought, this consent was regularly acquired under circumstances that were at best questionable. Additionally, the sale of reserve lands was consistently presented as being in the long-term interests of the reserve communities, although it was railway and corporate executives and other members of the settler elite — including senior Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) and other public officials — who gained possession of the alienated reserve lands during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[11] Some of these land sales continue to be the subject of land claims and court challenges.

The contradictions here are apparent. While Canada presented its policies as beneficial to Indigenous peoples, and while it maintained that its goal was to remake reserve residents into farmers, the best agricultural land was the first to be removed from First Nations’ control. Even the right to use modern farming equipment and to participate in training programs, farm organizations, and wheat pools like their non-Native neighbours were curbed by Canadian officials. Further, amendments were made to the Indian Act soon after its creation, and more strictly applied after the mid-1880s, whereby reserve residents were required to secure a permit before selling or giving away any goods located or produced on reserves or by reserve residents. While some, like Cree elder John Tootoosis (1899–1989), recognized the positive aspects of the permit system as a means to protect First Nations vendors and consumers, he nonetheless saw it as a “loaded gun” that was, in the end, turned against those it was ostensibly designed to protect. Certainly, there was ongoing resistance to all of this from Indigenous communities, but for the most part, the protests were disregarded in Ottawa.[12]

Restricting Movement and Cultural Practices

Most Canadians are secure in their right to move about freely and practice whatever form of spirituality they choose, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Canadian and church authorities went to some lengths to restrict both for those they defined as Indians. The kinds of activities allowed on ever-shrinking reserves were increasingly limited, restrictions were placed on movement, and cultural practices among reserve residents were policed and penalized. The suppression of liberty among Indigenous peoples was central to Canada’s Indian policy.

The Pass System

The confinement of Indigenous peoples to reserves was set in motion through the application of a matrix of laws, regulations, and policies meant to “elevate” reserve residents while advancing the interests of non-Indigenous settlers. In much of Canada, movement was limited through the vagrancy provisions of the Criminal Code or the restrictions against trespass in the Indian Act. However, in the region that became the Prairie provinces, the most notorious and comprehensive element of the restrictive matrix was implemented through a Federal Government policy known as the pass system. Under this initiative, a reserve resident was required to first secure a written pass from their Indian agent if they wanted to visit family or friends in a nearby village; check on their children at a residential school; participate in a celebration or attend a cultural event in a neighbouring community; leave their reserve to hunt, fish, and collect resources; find paid employment; travel to urban centres; or leave the reserve for any other reason.[13] According to Assiniboine Chief Dan Kennedy of the Carry the Kettle First Nation in Saskatchewan, “[t]he Indian reserve was a veritable concentration camp.”[14]

Official correspondence from the decade before 1885 reveals that procedures were already in place and that there was a will at all levels of the D.I.A., the North-West Mounted Police, and political hierarchies, including Prime Minister John A. Macdonald himself, to restrict Indigenous movement in the West. The Northwest Resistance of 1885 provided the justification for the application of a comprehensive pass system in the Prairie West, regardless of whether individuals or their communities were part of the resistance.

All of those involved in the implementation of the pass system understood that it had no basis in Canadian law. It was never included in the Indian Act or any other piece of Canadian legislation, which naturally put senior police officials in a difficult position. The regulations were at odds with settlers who relied on Indigenous labour and trade (and so opposed the restrictions), but high-ranking policemen also feared that they would be humiliated once Indigenous people recognized the pass system lacked a legal foundation and then chose not to comply with the policy. Generally, the NWMP/RNWMP/RCMP leadership preferred compliance by persuasion rather than by force, although individual officers were at times even more zealous than Indian agents, and chose to apply force when they felt it was necessary. Indigenous people naturally resisted their confinement to reserves and seem to have made little distinction between being persuaded to remain on, or return to, their reserves and being escorted back by a contingent of mounted policemen. They tended to choose to comply with the policy, or openly defy it, according their own judgment of the specific situation.

There is textual evidence that passes continued to be issued until after World War I, and oral evidence that the pass system remained in operation into the mid-1930s at least. Even though Canada never had the capacity to forcibly restrict all off-reserve movement, the will of both the police and the D.I.A. to do what they could in this regard—regardless of the lack of legal foundation—is evident, even if some in the upper echelons of the police were sometimes uncomfortable.

Cultural Restriction

Not only were Indigenous people restricted in their right to move about freely, even in their traditional territories, but also spiritual practices that were fundamental to personal and community identity and well-being — and that had been practiced since time immemorial — were targeted for suppression. State and church officials alike were intolerant of these practices, which they regarded as alien and immoral. Canadian and religious authorities also recognized that spiritual systems were integral components of the cultural, political, economic, and social structures of Indigenous communities. To transform one, the others had to be reconfigured as well.[15]

While there is evidence of this cultural repression across the country, the ceremonies of West Coast peoples known collectively as the potlatch received particular attention from politicians, missionaries, and government officials. The term potlatch refers to a complex of strictly regulated ceremonies that continue to be of critical significance to the Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish, Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Heiltsuk, and other peoples of the North West Coast of North America. The potlatch is the central institution that binds each of these societies together. Potlatches can be held to confirm leadership, alliances, or access to land and resources. Names (and, thus, status) can be given or passed down, debts repaid, dishonour erased, marriages performed, births announced, or the loss of loved ones memorialized. Potlatches provide a forum for history to be transmitted and verified, and gifts are given to witnesses who are obliged to remember and confirm what they have experienced. In addition to handling and healing earthly concerns, potlatches also have important spiritual components.[16]

Many in late 19th and early 20th century settler society who were fortunate enough to witness potlatch ceremonies first hand, or who benefited materially by providing supplies, supported their continuation. On the other hand, Indian agents who saw families working for months to meet the expense of a potlatch denounced the institution as “foolish, wasteful, and demoralizing.” It seemed to them that these ceremonies were held solely to give away material goods, a concept that was directly opposite to settler goals of capitalist accumulation and private property, and which simultaneously challenged settler understandings of what constituted “wealth.”[17] Missionaries, for their part, tended to see potlatches simply as a manifestation of evil. Thomas Crosby (1840–1914), who worked as a Methodist lay missionary to Coast Salish peoples of southern Vancouver Island and the lower Fraser Valley, from 1863 to the 1890s, said of potlatches, “Of the many evils of heathenism, with the exception of witchcraft, the potlatch is the worst, and one of the most difficult to root out.”[18]

In 1884, the Indian Act was amended to include a ban on the potlatch along with the expressly spiritual dances associated with Plains ceremonial practices. Unlike the pass system, the prohibition against these institutions and practices was backed up by the force of law that became ever more strict and comprehensive over time. Despite the legislative prohibitions, many communities felt they had no alternative but to continue to hold potlatches and dances, even if they went to considerable effort to make them more portable and keep them out of the view of missionaries and Indian agents. Even with these precautions, there was a wave of prosecutions and subsequent incarcerations soon after World War I. It wasn’t until 1951 that the prohibitions against Indigenous ceremonies were finally dropped from the Indian Act. Some of the masks and other spiritual objects confiscated during the period of the ban have since been returned to their owners, but many others remain in the hands of museums and private collectors.

Conclusion

Historians continue to debate the multiple and sometimes contradictory meanings of these treaties. Indigenous spokespeople often return to the theme of renewal of treaties, suggesting strongly that they believed these were arrangements subject to regular, perhaps annual, review. Certainly, all earlier agreements between fur trade companies and French and British imperial representatives across Ontario and the western interior of North America operated according to those principles. A once-and-for-all-time agreement that saps sovereignty from a people is neither a contract nor a diplomatic agreement: it is an unconditional surrender, and no one was signing off on that. Nothing could make that point more clearly than the Métis and Nêhiyawak protests that arose in the 1880s.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians [a.k.a. The Indian Act] 1876, §§ 3(3)–3(6).https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ/STAGING/texte-text/1876c18_1100100010253_eng.pdf

Battiste, Marie. “Resilience and Resolution: Mi’kmaw Education and the Treaty Implementation.” In Living Treaties: Narrating Mi’kmaw Treaty Relations, edited by Marie Battiste, 259–78.Sydney, NS: Cape Breton University Press, 2016.

Borrows, John. “Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government.” In Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada, edited by Michael Asch, 169–72. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997.

Craft, Aimée. Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty: An Anishnabe Understanding of Treaty One. Vancouver: UBC Press & Purich Publishing, 2013. See esp. Part One.

Kelm, Mary-Ellen and Keith D. Smith. Talking Back to the Indian Act: Critical Readings in Settler Colonial Histories. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Long, John S. Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010.

Miller, J. R. “Canada’s Historic Treaties.” In Keeping Promises: The Royal Proclamation of 1763, Aboriginal Rights, and Treaties in Canada, 81–104. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015.

Moore, Christopher. “George MacMartin’s Big Canoe Trip.” Ideas. CBC Radio, January 10, 2013. http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/george-macmartin-s-big-canoe-trip-1.2913267

Obomsawin, Alanis, dir. Trick or Treaty? 2014; Montréal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/trick_or_treaty/

Venne, Sharon. “Understanding Treaty 6: An Indigenous perspective.” In Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada, edited by Michael Asch, 173-208. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997.

Wicken, William C., and John G. Reid. “An Overview of the Eighteenth Century Treaties Signed between the Mi’kmaq and Wuastukwiuk Peoples and the English Crown, 1693–1928.” In Report Submitted To Land And Economy Royal Commission On Aboriginal Peoples 1996, 2–66. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services, 1996.

“William C. Wicken.” Canada’s History, November 19, 2013. http://www.canadashistory.ca/awards/governor-general-s-history-awards/award-recipients/2013/william-c-wicken

Williams, Alex. The Pass System. Tamarack Productions, 2015, http://thepasssystem.ca/

- The Mi’kmaq (especially the Mi’kmaq of Unimaki, or Cape Breton) regarded Paussamigh Pemmeenauweet as chief only of his people at Shubenacadie. There’s nothing to suggest that he regarded his position otherwise. Nevertheless, he and his people used this settler society title as best they could to effect change. ↵

- Ruth Holmes Whitehead, The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Micmac History 1500-1950 (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Limited, 1991), 218–19. ↵

- Arthur J. Ray, I Have Lived Here since the World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1996), 152–3. ↵

- Ottawa withheld from the three Prairie provinces control over resources and resource revenues until 1930. ↵

- Keith Smith, “11.6. Living with Treaties,” Canadian History: Pre-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. ↵

- On treaty-making in Canada across time, see J. R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009). ↵

- Cecile Many Guns and Annie Buffalo, “Interview with Mrs. Cecile Many Guns (Grassy Water) and Mrs. Annie Buffalo (Bear Child),” interview by Dila Provost and Albert Yellowhorn Sr., University of Regina, oURspace, 1973, http://ourspace.uregina.ca/handle/10294/586. ↵

- Sarah Carter, Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 118–27. ↵

- Keith Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance, and Resistance: Indigenous Communities in Western Canada, 1877–1927 (Edmonton, AB: University of Athabasca Press, 2009), 50. ↵

- Ibid., 132; Robert White-Harvey, “Reservation Geography and Restoration of Native Self-Government,” The Dalhousie Law Journal 17, no. 2 (1994): 588–589; Statement of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia for the Government of British Columbia (Vancouver: Cowan & Brookhouse, 1919) in LAC, RG 10, vol. 3821, file 59335, part 4A. ↵

- Robert Cail, Land, Man and the Law: The Disposal of Crown Lands in British Columbia, 1871–1913 (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1974), 14; Peggy Martin-McGuire, First Nation Land Surrenders on the Prairies, 1896–1911 (Ottawa, ON: Indian Claims Commission, 1998), 15–16, 42, 493–94, and 497–98. ↵

- Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 253–58 and 156–58; Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance, and Resistance, 99–103; Jean Goodwill and Norma Sluman, John Tootoosis (Winnipeg, MB: Pemmican Publications, 1984), 123–25. ↵

- This section on the pass system is drawn from Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance and Resistance, 60–77. ↵

- Dan Kennedy, Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief, ed. James R. Stevens (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1972), 87. ↵

- Katherine Pettipas, Severing the Ties that Bind: Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies (Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 1994), 3–4. ↵

- John Lutz, Makuk, 58. ↵

- Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, 2nd ed. (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1992), 206–7; Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 160. ↵

- Thomas Crosby, Among the An-Ko-me-nums or Flathead Tribes of Indians of the Pacific Coast (Toronto, ON: William Briggs, 1907), 106. ↵