Chapter 11: Renewal, Resurgence, Recognition—From White Paper to Armed Protest

As we’ve seen, resistance to settler colonialism took place at the community, household, and individual levels. There were many options available to Indigenous people and they were often seized upon, but scaling up resistance to a national or legislative response was nigh on impossible. Obstacles included Section 141 of the Indian Act, added in 1927, which made it illegal to raise funds for a court challenge to the federal government (precisely because Indigenous peoples were already mobilizing against colonialism). In a stroke, Ottawa had criminalized legal action in support of Aboriginal rights. Restrictions on free movement and the lack of access to financial resources were further barriers to building regional and national strategies among First Nations. Then, shortly after the Second World War, federal government and settler-society attitudes and positions began to shift. In 1951, Ottawa removed the barriers to raising funds for legal challenges; sanctions against the potlatch and other ceremonies were dropped; and steps were taken toward enfranchisement of “status Indians,” a step that some Indigenous people rightly feared would entail loss of status. In the two decades that followed, however, it became clear that Ottawa policy-makers had in mind assimilation by other means.

Electoral Reform

Democratic inclusion—the franchise—became, in the nineteenth century, the benchmark of real citizenship in many western countries. In Canada, as in the United States, Australia, Britain, and France, the vote was sought by groups such as working men, immigrants, and women. It was one token of inclusion, and its denial or termination was a sure sign of exclusion. The record of disenfranchisement in British Columbia provides a useful example of how electoral rights were bound up in ideas about race and gender. Indigenous people and Chinese immigrants in British Columbia had the right to vote until it was stripped from them in 1874; around the same time, women lost the right to vote at the civic level; Japanese immigrants and their descendants were disenfranchised in 1895; immigrants from India (lumped together as “Hindus”) lost the vote just as their numbers began to become substantial, in 1907, a year that witnessed race riots in Vancouver. Doukhobors, too, lost the vote—in 1931. Disenfranchisement was experienced as a slap in the face, just as it was intended.

The experience of Indigenous peoples overall was more convoluted. Provincial regulations—such as the disenfranchisement of Indigenous voters in British Columbia in 1874—were sometimes at odds with federal laws. Ottawa’s goal of assimilation is reflected in the 1876 Indian Act’s provision for the enfranchisement of Indigenous people who lost or relinquished Indian status, so long as they met the property qualifications of the time. Any Indigenous person who was seen to be legitimately practising medicine or acting as a clergyman (note: man) or lawyer, or who earned a university degree, would also be eligible. It is almost needless to say that few qualified under these conditions. The rules were tweaked in the revised Indian Act of 1880 and in the Indian Advancement Act of 1884. The Electoral Reform Act of 1885 granted the franchise to any land-owning Indigenous male in Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. (War between the Canadian state and Indigenous peoples on the Western Plains in 1885 explains these geographic constraints.) Thirteen years later, these eligibilities were stripped away. (The irony here, worth noting, is that the franchise—limited though it was—had been granted by John A. Macdonald’s government, and in 1898 the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier feared that grateful, pro-Conservative Indigenous voters in central and eastern Canada would tip the balance against Liberal candidates.)

There has probably been no time in the history of Canada before or since when so much concerted effort on Ottawa’s part was put into assessing and reshaping Indigenous lives. The timing—the second half of the Victorian era—is important. This was an age of state-making and, as has been pointed out elsewhere, “the state is in the business of making citizens.”[1] According to the 1996 Royal Commission, in the late nineteenth century:

. . . the federal government took for itself the power to mould, unilaterally, every aspect of life on reserves and to create whatever infrastructure it deemed necessary to achieve the desired end — assimilation through enfranchisement and, as a consequence, the eventual disappearance of Indians as distinct peoples. It could, for example, and did in the ensuing years, control elections and the conduct of band councils, the management of reserve resources and the expenditure of revenues, impose individual land holding through a ‘ticket of location’ system, and determine the education of Indian children.

This legislation early in the life of Confederation had an even more wide-ranging impact. At Confederation two paths were laid out: one for non-Aboriginal Canadians of full participation in the affairs of their communities, province and nation; and one for the people of the First Nations, separated from provincial and national life, and henceforth to exist in communities where their traditional governments were ignored, undermined and suppressed ….[2]

The tide turned again in 1917 for status Indians serving overseas during the First World War.[3] They obtained the right to vote in Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden’s cynical attempt to get a renewed mandate and support for conscription. The Indigenous soldiers’ franchise, however, evaporated on their return home. Similar provisions would be made in the Second World War, arising in some measure from a more widespread settler society concern for poor conditions on reserves. It also reflected international developments and the impact of wartime propaganda and rhetoric that favoured liberal-democratic values. By 1939, Canada was one of a shrinking number of liberal-democracies left standing. Authoritarian regimes and dictatorships were springing up everywhere. The war pitted nation-states and economic empires against one another. It also created a discourse of democracy-versus-dictatorship, a narrative that continued into the post-1945 period and the Cold War. By this point, all adult women and men in the white settler community were enfranchised; in 1947 and 1949, the vote was extended to the Chinese, South Asian, and Japanese communities. Change was slower to come as regards Indigenous voting rights.

A post-war Special Joint Committee on the Indian Act in 1946 provided a rare forum for Indigenous leaders to speak to their many concerns. As regards the franchise, they were wary of anything that would undermine Indian status, tax exemption, and treaty rights. Despite the Joint Committee’s recommendations in favour of enfranchisement, successive federal governments hesitated, increasingly fearful of the impact status Indian voters would have on their electoral chances. Put plainly, they withheld democratic power because it might actually be used to express democratic will. In 1950, Indian Affairs shifted into the Department of Citizenship and Immigration, and for the next sixteen years the official position of Ottawa’s bureaucracy was that Indigenous peoples were “immigrants too” and had to be “Canadianized.”[4] The election of the Conservative government in 1957 led to further change. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker—the MP from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, a riding with a significant Indigenous population—championed the idea of inclusion and rights that extended to all Canadians. Status Indians got the franchise in 1960 without the feared corollary of loss of status. While it is true that Inuit were able to vote as early as 1950, the difficulties of polling a widely-dispersed and mobile population meant that, in practical terms, there was little in the way of Canadian electoral democracy in the far north until the early 1960s.

For many Indigenous people, the 1960 franchise was a welcome change and one that was long overdue. Indigenous soldiers in two world wars had experienced rights and a degree of inclusion that they typically lost on return to Canada. They were allowed to drink with their comrades when at war but barred from beer parlours once back home, for example. While cafés and restaurants in towns like Prince George had a reputation for inclusion, Indigenous people were regularly excluded in Penticton and hauled out of coffee shops in Vanderhoof by the RCMP.[5] The franchise went some way to ameliorate a sense of being second-class citizens, particularly among those Indigenous peoples who lived in urban or semi-urban areas, graduated from high schools alongside white settler “citizens,” and engaged in businesses that were impacted by local, provincial, and federal laws.

For others, while it was not necessarily a poisoned chalice, democracy was viewed as a kind of misdirection. Why would a people who were sovereign in their own right seek inclusion in a state that defined, regarded, and treated them as “wards”? What if democratic inclusion was just a precursor to assimilation into the larger Canadian project? These were questions that were sharpened to a fine point in the early days of Pierre Trudeau’s government.

White Paper, Red Paper

Jennifer Pettit summarizes the course of reform of Ottawa’s policies in the 1960s and ’70s and, just as importantly, its approach to and philosophy as regards Indigenous people and issues.

“Citizens Plus” — The 1960s (CC BY 4.0)[6]

Jennifer Pettit, Department of Humanities, Mount Royal University

A stand-alone Department of Indian Affairs was created in 1966. Another significant event was the Hawthorn-Tremblay Report entitled A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies. Based on a series of cross-Canada consultations, the 1966-1967 Hawthorn Report concluded that Canada’s First Nations were marginalized and disadvantaged due to misguided government policies like the residential school system (which the Report recommended closing). Hawthorn argued that Indigenous peoples needed to be treated as “Citizens Plus” and provided with the resources required for self-determination. As a result of this report, the Canadian government decided to take policies in an entirely new direction, which were outlined in the White Paper of 1969.

In the White Paper, the stated goal of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien, Minister for Indian Affairs, was to achieve greater equality for Canada’s First Nations. The White Paper called for an end to Indian status, the closure of the Department of Indian Affairs, the dismantling of the Indian Act, the conversion of reserve lands to private property, and immediate integration. While the federal government believed this to be desirable, Indigenous groups across Canada were outraged, and argued that forced assimilation was not the means to achieve equity and that the White Paper had not addressed their concerns. They responded with a document called Citizens Plus, which became known as the Red Paper. In the Red Paper, Indigenous peoples stressed the importance of land and upholding the promises made in the treaties, and called for political organization. In response, the government withdrew the White Paper in 1970.

Reforming the Indian Act

Clearly, Indigenous political leaders had real qualms about the Indian Act, as did those in the settler community who sought a more inclusive society. The Indian Act, however, remains a problematic knot that binds the First Nations and non-Indigenous communities together.

In 1983, a Special Parliamentary Committee on Indian Self-Government (referred to as the Penner Report) recommended to Ottawa a form of autonomy that represented to most Aboriginal leaders an advance on what had gone before it. The general election in 1984, however, brought in a Conservative government informed by neo-conservative fears of fiscal mismanagement and public dependency. Led by Brian Mulroney, the new administration proposed a kind of municipal level of self-government, one that would cut the need for (and costs of) guardianship that had existed for a century. To many Indigenous leaders, this looked like White Paper 2.0. Few were interested in decentralized responsibilities that relieved Ottawa while setting up the First Nations and provincial governments for conflict. Mistrust was sown, and one consequence would be the failure of the Meech Lake Accord in 1990 (discussed later in this chapter).

New Organizations

The political crisis generated by the release of the White Paper reinvigorated many existing Indigenous organizations. There was never just one strategy, nor just one avenue for change: policy changes were sought by some groups, social and cultural changes by others. The White Paper, however, necessitated a political response specifically, so Indigenous leaders and communities in Canada took their campaigns to the courts, to the legislatures and Parliament, to international forums, to the British Commonwealth, and to the streets. Harold Cardinal (1945–2005) produced a thoughtful and thorough critique of federal policy in The Unjust Society (1969), the title of which was a jab at Pierre Trudeau’s call for a “just society.” Two key organizations appeared at this time: the National Indian Brotherhood emerged from the split within the National Indian Council in 1967–68, and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs in 1969.[7] The Brotherhood was simultaneously a move to a larger, less provincial stage for what had been the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians and a break with the foremost Métis organization. This was one of many signals that the movement as a whole did not speak with one voice.

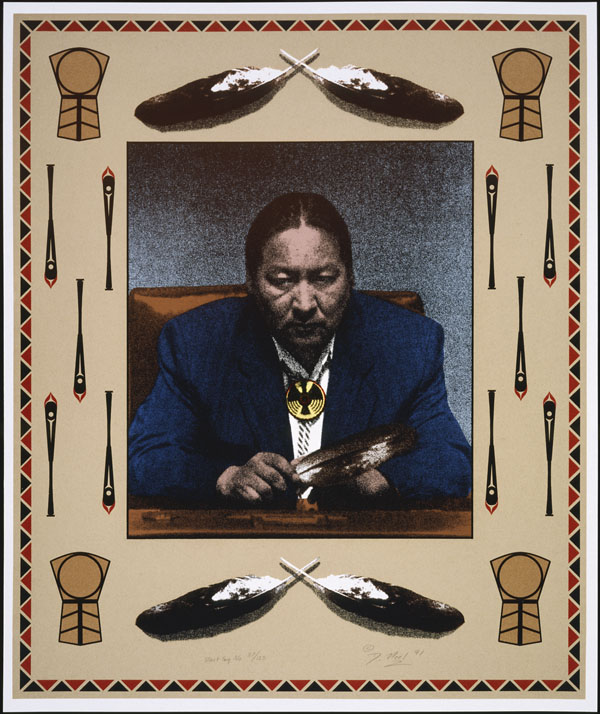

George Manuel and the Fourth World

A Secwépemc leader from Neskonlith on the South Thompson River, George Manuel (1921–89) emerged as both a spokesperson and a theorist. His conception of the “Fourth World,” a category of predominantly small and colonized Indigenous populations around the globe, resonated with those advocating for Indigenous rights, informed the thinking of Indigenous organizations in Canada generally, and contributed to the establishment of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples, which Manuel led in the mid-1970s. Manuel was able to secure federal funding for research into a variety of Indigenous claims and set the movement on a solid financial footing for the first time.[8] In the 1980s, as the Western world was convulsed with protests against apartheid in South Africa, Manuel was able to provide the intellectual firepower for a broader dialogue on oppressed peoples globally. In many respects, the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is a fruit of Manuel’s labours.

The National Indian Brotherhood pursued the goal of self-governance for Indigenous communities. This agenda worked best for First Nations that had treaty rights. Those that did not were more likely to look for advancements in constitutionally–enshrined rights, specifically “Aboriginal rights.” The two were not mutually exclusive and sometimes were even complementary, but the benefits of autonomy for off-reserve, urban Indigenous peoples—and those who lost or never had status—were less clear-cut. There was broad agreement that education and social welfare were areas of responsibility that ought to be stripped from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). To be clear, this was at a time when the extent of abuses in the residential schools was known to few, and then only anecdotally; likewise, the scale and ramifications of the “Sixties Scoop” were not yet fully appreciated. The 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s saw band offices take on greater and greater responsibilities. A generation of more entrepreneurial band managers emerged in some locations. At the same time, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN)—established in 1982 as the successor to the NIB—worked with the Union of BC Indian Chiefs to secure recognition for Aboriginal rights in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This was no small victory.

Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982[9]

35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons.

In the Courts

Legal challenges to settler colonialism accelerated in the last thirty years of the century. A few landmark cases are worth citing here, beginning with the 1973 Calder case. The Nisga’a First Nation of British Columbia exhausted the provincial courts and then won a decision from the Supreme Court of Canada: title to their land had never been extinguished. Even though the Court was split as to whether Aboriginal title on the West Coast persisted after 1871, the federal government took the view that it did. The provincial government in Victoria disagreed and would drag its feet until an NDP government was elected in 1990. At that point, Victoria began negotiating a new generation of treaties. Since 1998, when the Nisga’a Final Agreement was reached, a handful of other post-Calder treaties have been negotiated under the BC Treaty Process—only three final agreements (involving the Tsawwassen, Maa-nulth, and the Tla’amin First Nations) have been finalized.

There was a similar return to treaty negotiations in Québec. In 1911, the province annexed the Ungava Peninsula, extending its boundaries across Inuit and Innu (a.k.a. Montagnais and Naskapi Cree) territories. Treaty negotiations were meant to occur, but they did not. First Nations were relocated from areas where massive hydroelectric projects were being built, despite protests. Then, in 1973, the provincial courts declared that negotiations were still mandatory. In contrast to the slow progress made in BC, by 1975 an agreement with the Grand Assembly of the Cree and the Northern Québec Inuit Association was in place.

What Calder and the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement demonstrated was the utility of the courts in achieving Indigenous goals. Smaller victories were secured in increments and then, in 1990, another watershed was crossed. Ronald Sparrow, a fisherman and member of the Xwméthkwiyem (a.k.a. Musqueam or xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) First Nation, was caught (in 1985) using a drift net larger than what was permitted under the Fisheries Act. Sparrow challenged the charge itself, claiming that Section 35(1) exempted Indigenous fishers from federal and provincial regulations. The case made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, where Regina v Sparrow produced a unanimous decision that any activity or “right” that existed prior to 1982 continued, unless it had been explicitly and specifically extinguished. This was the first significant test of constitutional Aboriginal rights and an important win for First Nations.

Elijah Harper and Constitutional Reform

The Meech Lake Accord (1987) was meant to provide an amending formula to the Constitution Act of 1982. It required approval by Ottawa and each provincial legislature. First Nations consultation, however, was meagre, and many Indigenous leaders were outraged. Elijah Harper (1949–2013), an NDP member of the Manitoba legislature, made use of legitimate procedural delays to ensure that the legislature was unable to take a vote on the Accord until the deadline for approval had passed. Harper was the first “treaty Indian”in provincial office in Manitoba, a quiet force whose determined “No” drew breathless national attention to Indigenous issues. The absence of any language addressing Indigenous needs and authority in the Accord stood in sharp relief to the “distinct society” clause for Québec. After Harper, consultation and inclusion—though still far from perfect—improved.

The 1990s were, indeed, a busy decade in the courts. Delgamuukw v British Columbia saw the Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en First Nations initially frustrated badly. In 1991, Chief Justice Allan McEachern declared that Aboriginal rights only existed because the settler regime said they did. MacEachern also dismissed oral histories as unreliable. In 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada declared that McEachern was wrong on both counts. As regards oral history, the Supreme Court said:

Notwithstanding the challenges created by the use of oral histories as proof of historical facts, the laws of evidence must be adapted in order that this type of evidence can be accommodated and placed on an equal footing with the types of historical evidence that courts are familiar with, which largely consists of historical documents.[10]

Moreover, Delgamuukw clarified the laws on Aboriginal title. Echoing language in the Proclamation Act of 1763, the Court decided that title exists and specified the test for proving it.

The trends in Sparrow and Delgamuukw continued into the twenty-first century. Haida Nation v British Columbia in 2004 and Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia in 2014 addressed the use of natural resources within unceded traditional territories. Haida took forty years to come to a conclusion—in the BC Court of Appeals this time—and Tsilhqot’in required a visit to the Supreme Court of Canada. But the effects were significant: no natural resources may be harvested/extracted on traditional lands without consent of the relevant First Nation(s). Tsilhqot’in is significant, too, in that it acknowledged title to a specific and large land base for the first time.

The trajectories of these cases reflect the form of Canadian federalism: natural resources, except for fisheries, are a provincial responsibility. So long as provincial revenue streams rely on stumpage fees, hydroelectricity sales, and mineral royalties, there is an incentive for Victoria, Edmonton, Québec City, or St. John’s to advocate for unfettered access. By contrast, Fisheries Canada plays a role that ostensibly supports both industry and conservation. In practice, however, Fisheries Canada has met its conservation targets not by heavily regulating industrial fishing operations, but by placing restrictions on Indigenous fishing rights. Where we see a greater congruence between the interests of Ottawa and the provinces lately has been in the realm of oil pipelines: the movement of goods across provincial boundaries is a federal jurisdiction. This has pitted the oil patch (and, to some degree the National Energy Board) against the interests of several First Nations.

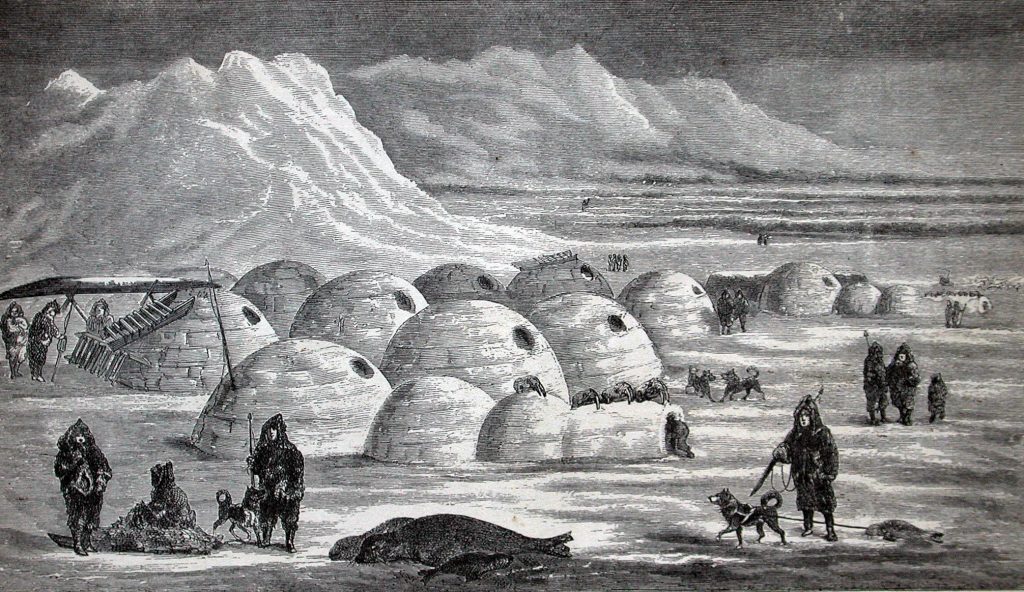

Nunavut

In the late 1970s, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami of Canada (called, at the time, the Inuit Tapirisat) and the government of Canada began negotiations over claims to the eastern third of the NWT. A separate, autonomous Inuit administrative unit—unique in the spectrum of Indigenous communities in Canada—was designed and then confirmed in a 1982 referendum. In 1992, the complex Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act was concluded, and the new Nunavut Territory emerged. Inuktitut is the first official language of the new jurisdiction, wherein about four-in-five are Inuk.

Extra-Legal Protests

Litigation wasn’t the only route taken by Indigenous activists and leaders. Inspired by the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the African-American civil rights movement, some (typically younger) Indigenous men and women were drawn to the “Red Power” movement. Road blockades, public demonstrations, the occupation of government and agency offices, and other “direct action” tactics were deployed. Protests in the 1970s were, in some instances, effective. Dene blockades in the Northwest Territories put the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline on ice, pending the findings of a Royal Commission (1974–77). The Commission chair, Justice Thomas Berger, recommended that Ottawa make extensive land settlement agreements with Indigenous peoples in the region and that there be a moratorium on the pipeline in the meantime. Anti-Québec Hydro protests in northern Québec similarly pit Indigenous peoples against major infrastructure projects. The confrontation there between Innu and Inuit on the one hand and the province of Québec on the other, however, had the added effect of hardening Indigenous feeling against the Québec separatist movement (and vice versa). Some of these sentiments could be perceived in later events at Oka.

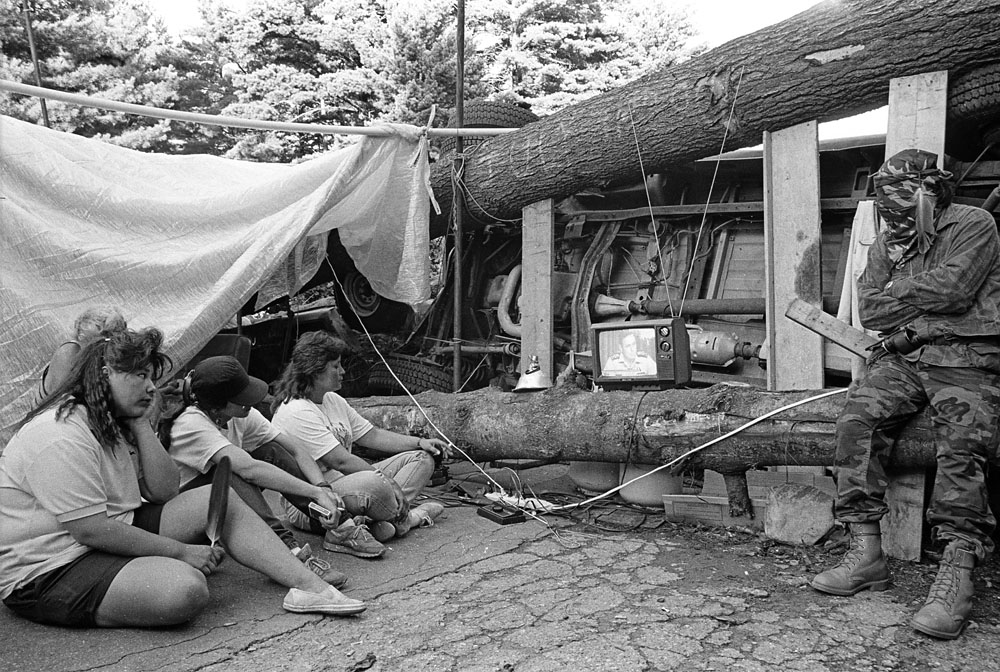

More widely known for its distinctive cheese, the village of Oka in 1989 approved plans to expand a private golf course. The land in question had been the subject of centuries of disputes between successive colonial regimes and the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) of Kanesatake. Some of the land involved included Indigenous burial sites. A nine-hole golf course was built in 1961—in the face of Kanien’kehá:ka opposition—so Oka’s efforts to double the size of the course in the late ’80s was a renewal of conflict and not something new. The Kanien’kehá:ka responded to this development with a blockade and demonstration. A sympathy blockade on the Mercier Bridge into Montréal by the Kanien’kehá:ka community at Kahnawake soon appeared. A firefight at the first blockade resulted in the death of a corporal of the Sûreté du Québec, putting the confrontation on television screens around the world. From a core group of fewer than three dozen, the protest rapidly grew to include six hundred. The RCMP joined the Sûreté, as did the Canadian Armed Forces’ Royal 22nd Régiment (the “Van Doos”—a historically francophone/Québecois regiment). The standoff ran for nearly three months, with mixed results. Ottawa purchased the land in question from the developers, but the courts have steadfastly rejected Kanesatake’s claims.

The Oka Crisis served to inspire further direct action. Five years later, in the summer of 1995, Secwépemc spiritual leaders sought to hold an annual Sun Dance near Gustafsen Lake (a.k.a. Ts’Peten). As relations deteriorated between the Secwépemc and the local rancher-settler who claimed the property, Indigenous and non-Indigenous allies gathered in growing numbers, and the RCMP (replete with armoured personnel carriers, helicopters, and as many as four hundred tactical squad members) were deployed. The RCMP also engaged in a campaign of disinformation designed to limit public sympathy for the protesters. Assurances that the protesters would be allowed to leave the site unmolested were broken, and many were arrested: fifteen individuals received sentences of six months to eight years.

Concurrently, another protest was underway at Ipperwash Provincial Park at the south end of Lake Huron. There, the dispute focused on a stretch of shoreline containing an Anishinaabeg burial site that had been expropriated from reserve lands under the War Measures Act during World War II. In 1994, members of the Kettle Point band initiated a round of occupations and protests to remind authorities that this issue was still on the table. A more formal and sustained protest began in September 1995. At the outset, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) attempted to achieve a negotiated outcome so as not to repeat the mistakes of Oka, or to echo events underway in BC. This approach did not last long: riot police with shields, batons, and helmets were deployed. On 6 September, the two sides confronted one another in the park; events quickly spiralled out of control. As at Oka and Ts’Peten, there was gunfire, and Dudley George (1957–95) was struck three times by a police sniper. Attempts to get George to a hospital were blocked by the OPP, and the man bled out. The police sniper was subsequently tried and found guilty of criminal negligence. The Ontario Provincial Government, led by Conservative Premier Mike Harris (b. 1945), was resolutely opposed to the Anishinaabe protest. Harris was quoted by his attorney-general as saying “I want the fucking Indians out of the park.”[11] Twenty-one years on, a deal was struck between the federal government and the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation (CKSPFN), which will lead to the eventual return of the land to the CKSPFN. The decontamination of the site and the removal of explosive ordinance advances only very slowly.[12]

At Burnt Church, a Mi’kmaq community at the mouth of the Miramichi River in northeastern New Brunswick, another protest led to violence that has been described as a community-wide civil war. The catalyst in this instance was the Aboriginal right to harvest reasonable quantities of lobster “out of season.” As was the case with Sparrow, the Mi’kmaq argued that constitutional Aboriginal rights protected their practices. Commercial lobster trappers from the settler community attacked Mi’kmaq traps and equipment, and by 2002 the Department of Fisheries had become an aggressor, attacking Mi’kmaq boats as the whole region plunged into chaos. In the end, the Mi’kmaq won their point, but at the cost of a deeply fractured community.

Forty years of active resistance and protest have shown that confrontation can sometimes get a good result. As well, blockades and occupations had the additional advantage of becoming increasingly newsworthy—precisely because they were increasingly dangerous. From Oka through Burnt Church, protests were met with expressions of settler society power in the form of police forces, military, bureaucracy, and strident public (settler) opposition. In the win-loss columns, it mostly looks like a poor strategy, but as a means of keeping Indigenous issues in the public eye, galvanizing Indigenous community support, and drawing a line in the proverbial sand, the verdict is not so conclusive.[13]

Conclusion

The issues that cried out for resolution in Indigenous communities and in the relationship between treaty peoples were (and are) many and varied. The post-WWII era witnessed an acceleration and intensification of visible conflict and negotiation, in part because the constraints placed on Indigenous protest were lifted at mid-century. It is also a consequence of accumulating grievances paired with a shrinking margin on which Indigenous communities might continue. Any loss of land, resources, or personnel at this stage can be catastrophic to peoples whose ancestral territories and means of living were substantially reduced under colonialism. Repair to the fabric of damaged communities is called for at several levels. The next chapter explores some aspects of the health crisis on reserves and in the Indigenous population generally and how it is, ultimately, a crisis of history.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

Belanger, Yale D., and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, eds. Blockades or Breakthroughs?: Aboriginal Peoples Confront the Canadian State. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University, 2014. See esp. pp. 3–69, 166–221, 253–382.

Clements, Marie, dir. The Road Forward. 2017. Montreal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/road_forward/

Coates, Kenneth S. “Reclaiming History through the Courts: Aboriginal Rights, the Marshall Decision, and Maritime History.” In Roots of Entanglement: Essays in the History of Native-newcomer Relations, edited by Myra Rutherdale, Kerry Abel, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, 313–34. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Dennis, Darrel. “ReVision Quest Looks at Oka 20 Years Later.” Produced by Wabanakwut Kinew. CBC Radio, ReVision Quest, July 14, 2010. Podcast, mp3 audio, 28:16. http://podcast.cbc.ca/mp3/podcasts/revisionquest_20120918_38255.mp3

Knickerbocker, Madeline Rose, and Sarah Nickel. “Negotiating Sovereignty: Indigenous Perspectives on the Patriation of a Settler Colonial Constitution, 1975–83.” BC Studies, 190 (2016): 67–87.

Lambertus, Sandra. Wartime Images, Peacetime Wounds: The Media and the Gustafsen Lake Standoff. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Manuel, George, and Michael Posluns. The Fourth World: An Indian Reality. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Maracle, Lee. Bobbi Lee, Indian Rebel. Toronto: Women’s Press, 2017.

Nickel, Sarah A. Assembling Unity: Indigenous Politics, Gender and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019.

Obomsawin, Alanis, dir. Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. 1993. Montréal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/kanehsatake_270_years_of_resistance/

Obomsawin, Alanis, dir. Is the Crown at War with Us? 2002. Montréal: National Film Board. https://www.nfb.ca/film/is_the_crown_at_war_with_us/

- Cairns, “Aboriginal Research in Troubled Times,” 407. ↵

- Dussault et al., Royal Commission, 166. ↵

- For a summary of the experience of Indigenous soldiers in the twentieth century, see Scott Sheffield, “Status Indians and Military Service in the World Wars,” Canadian History: Post-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 6.12. For a more fulsome account, see Sheffield’s book, The Red Man’s on the Warpath: The Image of the “Indian” and the Second World War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004). ↵

- Heidi Bohaker and Franca Iacovetta, “Making Aboriginal People ‘Immigrants Too’: A Comparison of Citizenship Programs for Newcomers and Indigenous Peoples in Postwar Canada, 1940s–1960s,” Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 3 (September 2009): 427. ↵

- Carstens, The Queen’s People, 224; Moran, Sai-k’uz Ts’eke, 75. ↵

- Jennifer Pettit, “WWI to 1970,” in John Douglas Belshaw, Canadian History: Post Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 11.8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- On this topic, see Sarah A. Nickel, Assembling Unity: Indigenous Politics, Gender and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019). ↵

- Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens. ↵

- Constitution Act, § 35 (1982). ↵

- Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010 at para. 84. File No.: 23799. ↵

- Sidney B. Linden, Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, Vol. 1 (Ontario: Government of Ontario, 2007), 363. ↵

- Christina Howorun, “22 Years after Fatal Shooting of Dudley George, Ipperwash Still Doesn’t Feel Like Home,” City News, August 15, 2017, https://toronto.citynews.ca/2017/08/15/exclusive-22-years-after-fatal-shooting-of-dudley-george-ipperwash-still-doesnt-feel-like-home/. ↵

- Elements of this section come from John Douglas Belshaw, “Canada and the Colonized, 1970–2002,” in Canadian History: Post Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 11.10. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. ↵