Chapter 13: Truth and Reconciliation

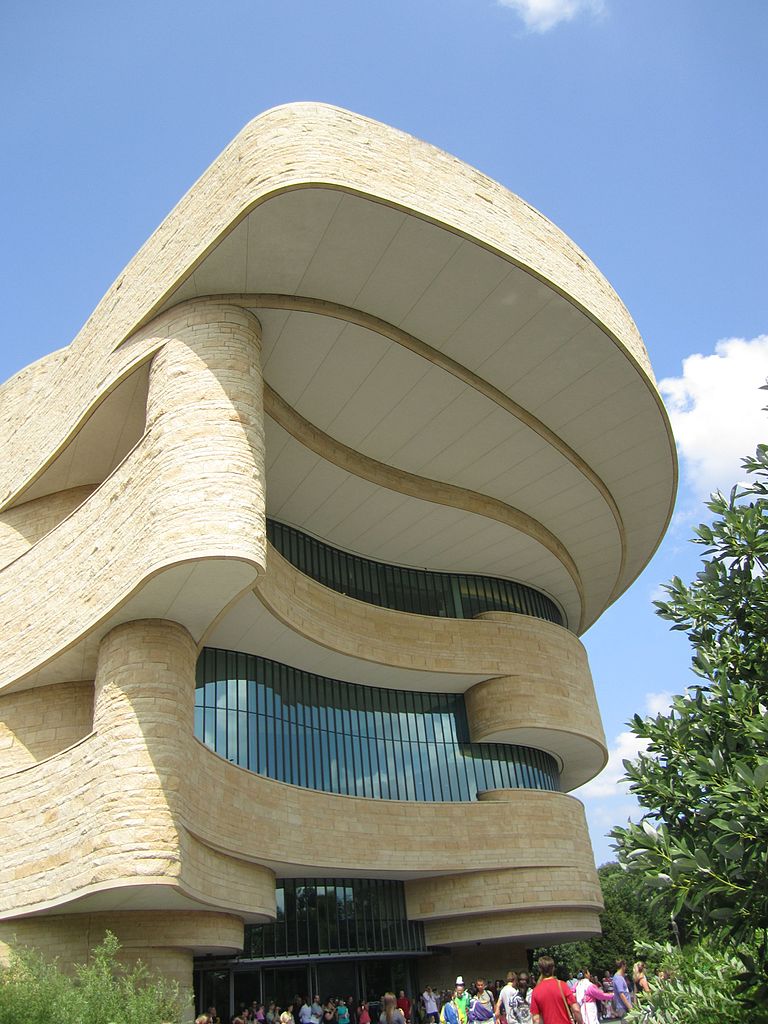

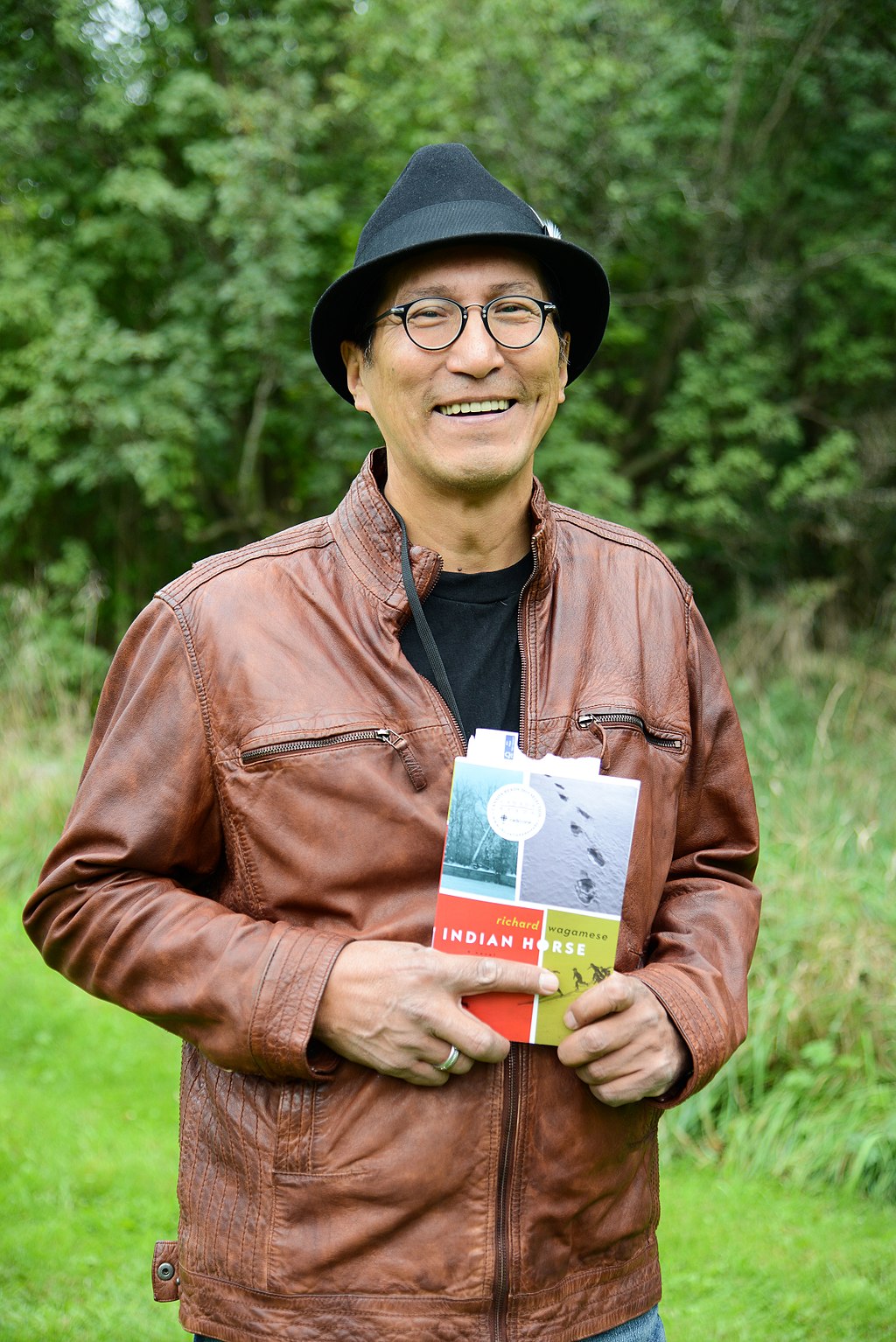

Twenty-first century Indigenous artists find ways to preserve traditional conventions while exploring new possibilities. Their successes are a reminder that the generation with which Canada must seek reconciliation is a millennial one. Consider these and other contemporary Indigenous artists/creators and the kinds of obstacles faced by their predecessors in colonial Canada. How has their indigeneity shaped them? How does their art express a reaction and resistance to colonialism?

More than a century of physical, political, and economic marginalization under colonialism impacted many aspects of Indigenous life. On the political front, these forces severely reduced the ability of Indigenous communities to collaborate as they sought redress. By the late twentieth century, however, modern communications systems—radio, television, film, and then the internet and social media—contributed to a revolution in Indigenous politics and diplomacy. The most outstanding example of that transformation was, of course, Idle No More. Mary-Ellen Kelm surveys the trail that began with apparent contrition on the part of Ottawa and led quickly to renewed frustration in Indigenous communities and then to rekindled protest.

Idle No More (CC BY 4.0)[1]

Mary-Ellen Kelm, Department of History, Simon Fraser University

On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper rose in Canada’s House of Commons to give an official apology for residential schooling. He called the treatment of Aboriginal children in the schools “a sad chapter in our history,” for which “the Government of Canada sincerely apologizes.”[2] Mr. Harper and the other party leaders expressed palpable remorse for the past injustices of Canadian policy, and leaders representing First Nations, Métis, Inuit peoples, women, and urban Aboriginal people gravely responded to the apology from the floor of the House.

For many Canadians, this promised to be a turning point in our relations with Aboriginal peoples. Until the 1990s when stories of abuse in the schools hit the media and the courts, most Canadians had never heard of the schools. Now the Prime Minister of Canada was admitting that a government policy had been wrong and that the attitudes that inspired the policy have “no place in Canada.” More importantly, he promised a new relationship between Aboriginal peoples and Canadians, one of shared history, renewed understanding, and new respect for all cultures, traditions, and communities.

Two processes were meant to bring this new relationship about. First there was compensation for those who attended the residential schools. Second, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was tasked with documenting the full history of the schools. Restorative justice scholars gave the Harper apology high marks.[3]

However, the apology was not a turning point. Its major failing was that it situated all the wrongs of government policy in the past. It did not commit the Canadian Government in any concrete way to changing its actions towards First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in the present. This was a significant mistake because a changed relationship with Canada was what Aboriginal people wanted.[4]

By 2008, Aboriginal people in Canada had already begun to shift the conversation between themselves and Canadians in really fundamental ways. In the twentieth century, Aboriginal people demanded government recognition of their rights and title to the land. As a new generation of Aboriginal leaders arose, they increasingly sought resurgence — of their own cultures and communities — rather than recognition. They wanted a new relationship with Canada, the kind of relationship of sharing and mutual respect that their ancestors had expected when they signed treaties.

The trouble was that Aboriginal people have not shared equally in Canadian wealth. In some parts of Canada, Aboriginal people have poverty rates that are three times those of other Canadians.[5] Less money is spent on reserve schools and Aboriginal children are ten times more likely to end up in foster care.[6] So while Mr. Harper was apologizing for the damage done to Aboriginal children and families by residential schools, the legacies of residential schooling continued unabated.[7]

The Cree community of Attawapiskat has become emblematic of Canada’s dysfunctional relationship with Aboriginal people. An isolated community on the shores of James Bay, Attawapiskat made the news repeatedly in the early 2000s. Its only school was condemned as a health hazard, and student Shannen Koostachin took her demands for a new school to Ottawa in 2007. Four years later, Chief Theresa Spence (b. 1963) declared a state of emergency over inadequate housing. What made the situation worse was that the multinational corporation DeBeers was just 80 km away making a steady profit mining diamonds from Cree lands. The agreement DeBeers signed with Attawapiskat to share the mine’s benefits did not include infrastructure, such as schools and houses, because that was, DeBeers maintained, the responsibility of the Canadian government.[8] On December 11, 2012, Spence announced that she would go on a hunger strike to protest unfulfilled treaties.[9]

When Spence announced her hunger strike, she joined an already growing wave of protest and resurgence among Aboriginal people. The protest centred on government Bill C-45, a 457-page omnibus bill that loosened legal restrictions inhibiting investment in Canadian resources. The changes that C-45 introduced to the Indian Act, for example, made it easier to lease or surrender reserve land by removing the democratic requirement for a community-wide vote. First Nations were not consulted on any of these changes. Within a month of C-45’s first reading, on 10 November 2012, three Aboriginal women in Saskatoon (Sylvia McAdam, Nina Wilson, and Jessica Gordon, along with Sheelah McLean) conducted a teach-in on the bill, which they publicized under the name Idle No More.[10]

For the next six months, Idle No More exemplified Aboriginal resurgence. Social media was a major force in Idle No More: by May 2013, there had been over 1.2 million Twitter mentions of the #Idlenomore hashtag. The social media profile of Idle No More underscores an important feature of the movement: it was diverse and dispersed in its power and its leadership — not linked to any mainstream Aboriginal organization. Idle No More acknowledged the importance of women in Aboriginal communities, and they often took the stage at events. To honour her leadership, the movement rallied behind Chief Spence in her hunger strike.

To emphasize the social media component is, however, to miss the incredible live experience of the movement. Hundreds attended teach-ins across the country to learn more about Bill C-45, and how it violated treaty rights. Thousands marched on Parliament Hill on January 10, 2013 and participated in coordinated days of action across the country.

The Harper apology in 2008 and the subsequent findings of the TRC, released in 2015, have given Canadians ample reason to reflect on their failed relationship with Aboriginal people. Yet Aboriginal people ask not that Canadians focus on the past, but on the present and the future. TRC Chair, Chief Justice Murray Sinclair, has said that Canada will fail to uphold the spirit of the 2008 apology unless it commits to involving Aboriginal people in decisions about their lands and resources.[11] This too was Idle No More’s demand as the movement expressed renewed pride among Aboriginal peoples for their grassroots leadership and traditional methods of peaceful social change.

Truth and Reconciliation

The recommendations of the TRC include several that are germane to the study and teaching of history. Recommendation 62 identifies the development and implementation of mandatory K-12 curriculum “on residential schools, Treaties, and Aboriginal peoples’ historical and contemporary contributions to Canada.”[12] Such a curriculum will require not only a summary of current knowledge, but also an ongoing rethinking of what it is we think we know. Historians have entered into this process with optimism and, largely, humility. In 2005, the “Make Poverty History” campaign in Britain and Canada generated a sour response from historians: history makes poverty. Context—the burden of historical events—without doubt contributes to the marginalization and incarceration of Indigenous communities and individuals but, more than that, the way in which “history” is written also has an impact. The stories we tell frame the futures we imagine. Generations of settler histories and social studies curriculum laid a foundation of blinkered colonialism and racism. A recent study of the borderlands in the Pacific Northwest in the nineteenth century show how state-making consciously makes use of erasure as a strategy for defining colonial character. Outwardly benign-looking institutions like the Oregon Historical Society took steps in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to obscure Indigenous people as they produced heroic histories of the “pioneers,” a cohort that was defined by its American roots, Protestant faith, and whiteness. Regional inhabitants of mixed ancestral descent fared even worse. School curriculum, film, and even video games continue to contribute to this process of erasure, one in which historians are implicated.[13]

With an eye to improving our track record, historians/historiographers like Susan Neylan have issued challenges to historical practitioners to take the settler out of the centre of Canadian history, to shake up the orthodox narrative, and to reposition the Indigenous story as something that is more than a dialectic of “natives and newcomers.”[14] Collaborations between Indigenous knowledge-keepers and scholarly historians are becoming both more common and more sophisticated. They have a high bar to meet. Some of the earliest collaborative works—including the three books that came out of the partnership between Okanagan elder Harry Robinson and UVic professor Wendy Wickwire, and Spuzzum: Fraser Canyon Histories 1808–1939 by Annie York with Andrea Laforet—set a high standard indeed. The last decade has seen the field expand dramatically. Paige Raibmon, a historian at UBC, models what is currently regarded as best practices in her collaboration with Elsie Paul, a Sliammon Elder. The same may be said for the Kwagu’ł Gixsam Clan partnership with Leslie Robertson.[15] Many of the academics in these pairings are anthropologists first and foremost, a pedigree that may enable them to more easily shed some of the burdens of scholarly historical traditions. This is certainly the case with the work of Robin and Jillian Riddington, who have worked extensively with the Dane-Zaa First Nations.[16] Sophie McCall, an English professor at Simon Fraser University, has examined the structures, ethics, and challenges of this kind of collaborative project and a great many more, including movies and other media representations.[17] Academic historians, however, continue to have a role to play, one that is unlikely to be taken up by social scientists.

Academic historians have the capacity to situate local historical experiences within larger historical milieus. Technological, environmental, political, and economic changes in the past inform human experiences, and historical scholars are alert to changes in contexts across short, medium, and long timelines. Indigenous historians in the academy have, in some instances, done the reverse: they have located the meaning of “larger events” in Indigenous experiences. A good example of this is The Creator’s Game, a study of lacrosse by Allan Downey (Dakelh, Nak’azdli Whut’en, and a history professor at McMaster University). Downey shows how this ancient game was appropriated for nation-building purposes by settler society and then reclaimed by Indigenous communities who were able to use it to assert identity, resilience, and the goal of self-determination.[18] Studies like these continue to reorient historical thinking. The view east—and north and west and south—from Turtle Island is an increasingly common perspective among historians. These shifts will produce a changed meta-narrative, one that reconciles the plethora of Indigenous histories with the contradictions inherent in the invention of the colonial nation-state. That is hardly a cure-all for Indigenous histories and Canada, but it opens the possibility of a refreshed vision and new questions.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

Downey, Allan. The Creator’s Game: Lacrosse, Identity, and Indigenous Nationhood. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018. See esp. Prologue and chap. 5.

Downey, Allan, and Susan Neylan. “Raven Plays Ball: Situating ‘Indian Sports Days’ within Indigenous and Colonial Spaces in Twentieth-Century Coastal British Columbia.” Canadian Journal of History 50, no. 3 (2015): 442–68.

Freeman, Victoria. “‘Toronto Has No History!’ Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City.” Urban History Review 38, no. 2 (2010): 21–35.

Hammond, Joanne. “Decolonizing BC’s Roadside History.” Culturally Modified, November 7, 2017. https://culturallymodified.org/decolonizing-bcs-roadside-history/

Leddy, Lianne. “Intersections of Indigenous and Environmental History.” Canadian Historical Review 98, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 83–95.

Maracle, Lee. “Goodbye Snauq.” West Coast Line: A Journal of Contemporary Writing & Criticism 42, no.2 (Summer 2008): 117–25. Reprinted in Talking Back to the Indian Act: Critical Readings in Settler Colonial Histories, edited by Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith, 188–99. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Miller, Bruce Granville. “Conceptual and Practical Boundaries: West Coast Indians/First Nations on the Border of Contagion in the Post-9/11Era.” In The Borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: Essays on Regional History of the Forty-Ninth Parallel, edited by Sterling Evans, 49–66. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Miller, J. R. “Residential Schools and Reconciliation.” Active History. Accessed September 26, 2019. http://activehistory.ca/papers/history-papers-13/

Miller, J. R. Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, 4th ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. See esp. chap. 17.

Peers, Laura, and Robert Coutts. “Aboriginal History and Historic Sites: The Shifting Ground.” In Gathering Places: Aboriginal and Fur Trade Histories, edited by Carolyn Podruchny and Laura Peers, 274–93. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010.

Peters, Evelyn. “Our City Indians: Negotiating the Meaning of First Nations Urbanization in Canada.” Journal of Historical Geography 30 (2002): 75-92.

Stanger-Ross, Jordan. “Municipal Colonialism in Vancouver: City Planning and the Conflict over Indian Reserves, 1928–1950s.” Canadian Historical Review 89, no. 4 (2008): 541–580.

Vowel, Chelsea. “A Rose by Any Other Name Is a Mihkokwaniy.” âpihtawikosisân, January 16, 2012. http://apihtawikosisan.com/2012/01/a-rose-by-any-other-name-is-a-mihkokwaniy/

- Mary-Ellen Kelm, “Idle No More,” in John Douglas Belshaw, Canadian History: Post Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), section 11.12. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- Stephen Harper, “Statement of Apology to Former Students of Indian Residential Schools,” House of Commons, Ottawa, June, 11, 2008, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/ 1100100015649. ↵

- Sheryl Lightfoot, “Settler-State Apologies to Indigenous Peoples: A Normative Framework and Comparative Assessment,” Journal of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association 2, no. 1 (2015): 33. ↵

- Beverley Jacobs, “Response to Canada’s Apology to Residential School Survivors,” Canadian Woman Studies 26, no. 3/4 (2008): 223. ↵

- Shauna MacKinnon, “The Harper ‘Apology’: Residential Schools and Bill C-10” (Winnipeg: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Manitoba Office, January 24, 2012); Aboriginal Children in Care Working Group, Aboriginal Children in Care: Report to Canada’s Premiers (Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secretariat, 2015), 45. ↵

- Don Drummond and Ellen Rosenbluth, “The Debate on First Nations Education Funding: Mind the Gap,” Working Paper, Queen’s University Policy Studies (Kingston: Queen’s University, December 2013); Aboriginal Children in Care Working Group, Aboriginal Children in Care, 7. ↵

- Aboriginal Children in Care Working Group, Aboriginal Children in Care, 6. ↵

- “Roots of Attawapiskat Crisis,” Kelly Crichton, Producer, 8th Fire: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples and the Way Forward, Documentary Series, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2012, accessed 8 December 2016, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2172306785. ↵

- The Kino-nda-niimi Collective, The Winter We Danced: Voices from the Past, the Future, and the Idle No More Movement (Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2014), 391. ↵

- Ibid., 390. ↵

- APTN National News, “PM Harper Has Failed to Live up to Promise of 2008 Residential School Apology: TRC,” June, 2, 2015, http://aptn.ca/news/2015/06/02/pm-harper-failed-live-promise-2008-residential-school-apology-trc/. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Ottawa: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), 7. ↵

- Allan K. McDougall, Lisa Philips, and Daniel L. Boxberger, Before and After the State: Politics, Poetics, and People(s) in the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018). ↵

- Susan Neylan, “Colonialism and Resettling British Columbia: Canadian Aboriginal Historiography, 1992–2012” and “Unsettling British Columbia: Canadian Aboriginal Historiography, 1992–2012,” in History Compass Journal 11, no. 10 (Oct 2013): 833–44, 845–58. ↵

- Leslie Robertson with the Kwaguł Gixsam Clan, Standing Up with Ga’axsta’las: Jane Constance Cook and the Politics of Memory, Church, and Custom (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012). ↵

- Their most recent (and most hefty) contribution is Ridington and Ridington in collaboration with elders of the Dane-Zaa First Nations, Where Happiness Dwells. ↵

- Sophie McCall, First Person Plural: Aboriginal Storytelling and the Ethics of Collaborative Authorship (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011). ↵

- Allan Downey, The Creator’s Game: Lacrosse, Identity, and Indigenous Nationhood (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018). ↵