Chapter 8: Resistance II — Red River and Saskatchewan

The final chapter of this section deals with the dramatic breakdown of the treaty relationship in the late 1870s and early 1880s.[1] Not all Indigenous peoples on the Plains rose up against Ottawa, but all complained that their needs, rights, and entitlements were being neglected. There were fatal repercussions for doing so.

The path to the treaty table was, for Indigenous peoples in the West, a traumatic one. Nearly a century of transition to the mounted, bison-hunting culture was intermittently punctuated by outbreaks of epidemics of imported diseases. The worst took place in the 1780s and the 1830s. The latter cleaned out the Mandan-Hidatsa villages and marketplace. In that instant, the commercial and diplomatic balance of the Plains peoples was disrupted. Smallpox also affected the Nakoda Oyadebi (a.k.a. Assiniboine) dramatically, and everyone else to some greater or lesser extent. American traders moved into the region, filling in some ways the vacuum left by the Mandan and bringing additional—almost insatiable—demand for bison hides. Rifles replaced the old flintlock guns. Beaver populations were hunted to the brink. The HBC’s monopoly in trade was effectively nullified in the 1840s. Wars between the much better armed US Cavalry and the Indigenous peoples of the lands south of the forty-ninth parallel were in full swing. The Sioux and the Niitsitapi moved freely back and forth across the “Medicine Line” (the forty-ninth parallel) and thus posed a threat to the ambitions of both Euro-North American nation states. Indigenous alliances strained, and some rivalries exploded. On 24 October 1870, the Nêhiyawak and Niitsitapi engaged in a bloody confrontation: the Battle of Belly River, near Fort Whoop-Up in what is now Lethbridge. At the time, there was no way of knowing that this was to be the last major confrontation between First Nations on the Northern Plains, but the fatalities made it decisive. The upset victory of the Niitsitapi over the Nêhiyawak (who lost as many as 300 warriors) was pyrrhic: both sides were rendered vulnerable to attack, starvation, disease, and despair.

Canadian trepidation about Indigenous and Métis affairs in the West was worsening in the years 1869–70. The Métis resistance at Red River had, after all, won provincehood for Manitoba—something that Ontario’s leadership deeply resented. For many Ontarians, the entire point of confederation was gaining Rupert’s Land so as to settle surplus population there. There was suspicion in Ottawa that the Métis might have further plans and the ability to upset Canadian ambitions. As for the Nêhiyawak, Niitsitapi, and Anihšināpē of the southern Prairies, the Canadians could be only less certain. Somehow that threat would have to be diminished. The solution, of course, was treaties. Ottawa’s approach to the Métis, however, was punitive.

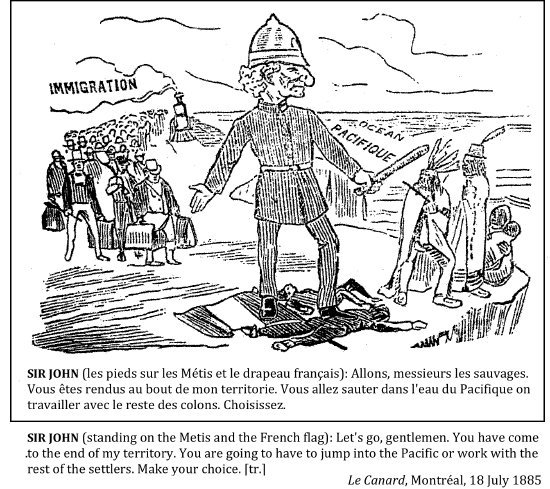

There was no love lost between the Métis and the English- and Protestant-Canadians, and the federal government believed that it had met all obligations undertaken in 1870 as regards the historic residents of Red River. Ottawa consistently refused to fold Métis communities—scattered after 1870 in a diaspora across the West—into the numbered treaties, even when requested to do so by Indigenous negotiators. When Métis protests resumed in 1885, the Anglo-Canadians in particular were inclined to see it as evidence of insatiable greed on the part of a population too feckless to get on with successful farming.

Not all Canadians shared the priorities and prejudices of Ottawa. There was sympathy in Québec for the Métis, who were viewed in some measure as part of a francophone and Catholic family. Some Anglo-Canadian settlers in the West, perhaps surprisingly, also sympathized and shared in the grievances registered by the Saskatchewan Métis. The original course of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was to come north through the Saskatchewan River valleys, where the best farmland was to be found. Canadian migrants had rushed into the area as a consequence, and the CPR’s decision to use the southern route instead left them hundreds of kilometres from a rail link. Among the leaders of the “Métis” uprising were Ontarian-westerners who criticized Ottawa’s arbitrary behaviour and the duplicity of the CPR. While some were less sympathetic than others, former HBC employees—who had a longer-term perspective on Nêhiyawak, Nakoda Oyadebi, and Niitsitapi societies—decried the state of affairs and the worsening condition of Indigenous peoples.

The Indigenous West[2]

From an Indigenous perspective, treaty promises of medicine chests, agricultural instruction, annuities, and food were consistent with the gift-giving diplomacy of past generations; offered up emergency relief in the face of hardship from famine or disease; and purchased peace. Some Indigenous leaders refused to sign, mostly because they recognized that the treaties didn’t really promise land; instead, the treaties proposed to take all of the land away, except for a small amount that would be marked on maps as reserves. Other Indigenous negotiators understood the treaties as creating exclusive lands—reserves—and the rest would be shared, perhaps held in common. There was confusion, clearly, but reluctance and caution were swiftly worn down by hunger.

The crisis that brought the Indigenous peoples of the Plains to the treaty table in the 1870s was rapidly worsening. What was left of the bison herds was, in the 1880s, under assault by better-armed hunters (Indigenous and otherwise). The repeating rifle was only one of several technological innovations that would severely compromise the remaining herds, most of which were now huddled in the southwest corner of Alberta. But even the Niitsitapi Confederacy could no longer count on this resource. By 1879, even the Cypress Hills resource was largely played out.[3] What had only decades earlier been a continental population of hundreds of thousands of Plains bison was reckoned to have plummeted to a few hundred in the early 1880s. It wasn’t so much the case that the clock was ticking; for the Cree and their neighbours, alarm bells were ringing.

Additional pressure was applied on the food stocks of the Plains by the arrival of refugees in the 1870s and 1880s. The crisis began in 1877, when the Lakota Sioux and their allies combined for one final push against the genocidal attacks of the US Cavalry. At Little Bighorn, they inflicted the most severe defeat that United States forces would suffer until Pearl Harbor. Nevertheless, Ta-tanka I-yotank (a.k.a. Sitting Bull, 1836–90) and his people were forced to flee to sanctuary across the Medicine Line. Their refugee camps were swollen with newcomers in the years that followed, and by 1880 their plight was desperate.

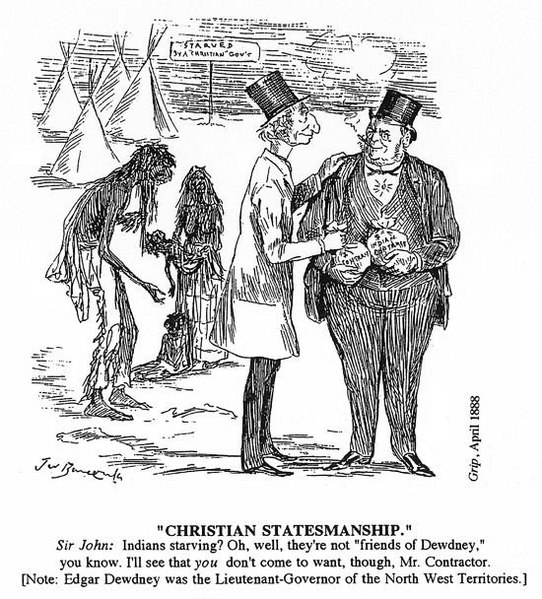

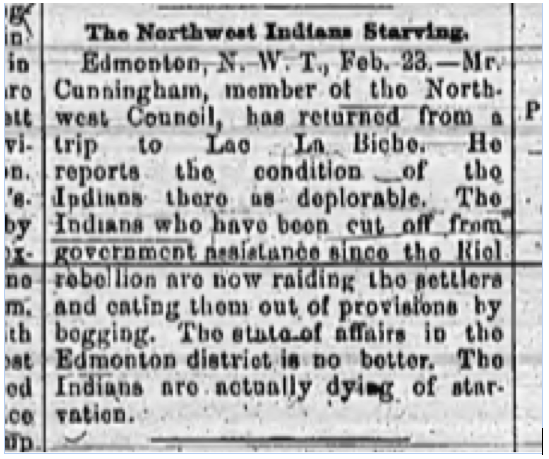

Beginning in 1879, famine swept repeatedly across the Prairies. Provisions promised under treaty were not supplied. What cattle that did arrive on the Plains to be used as draught-animals were, instead, eaten. The Nêhiyawak, Nakoda Oyadebi, and Anihšināpē who conformed to Ottawa’s expectations and remained on reserve were, as a consequence of their choice, vulnerable to starvation when Canada failed to meet its obligations. Those who rejected treaty and the reserves—including Nêhiyawak under the leadership of Piapot (1816–1908), Mistahimaskwa (a.k.a. Big Bear, 1825–88), and Minahikosis (a.k.a. Little Pine, 1830–85)—faced hardship just the same. What’s more, Ottawa exploited these conditions to try to push the recalcitrant factions onto reserves and into a European-style regime of agriculture. To be clear, Canadian authorities knew that famine was on the march. They had resources warehoused nearby, and yet withheld supplies in order to achieve a political goal: the submission of the Nêhiyawak and their neighbours to Canadian authority.

The situation was no better for the Niitsitapi. Reports of twenty-five starvation deaths in the last days of 1879 signalled that the last refuge of the bison was also in peril. Successive hard winters compounded conditions for everyone in the southwest Prairies and along the foothills. Despite fears of American attacks, many of the Niitsitapi relocated to the United States in pursuit of food or, perhaps, rations.

Resistance to taking treaty was crumbling. In 1879, Minahikosis signed Treaty 6. He nevertheless worked for the remaining six years of his life to expand and draw together the reserve lands into a contiguous pattern so as to create a Nêhiyawak homeland. Ottawa, however, feared an “Indian Territory” which might enable the growth of stronger political and military resolve. As a result, the Nêhiyawak reserves were chopped into smaller and more distinct parcels. This approach, of course, made the administration of aid still more difficult. What’s more, these now concentrated populations created promising conditions for epidemics to emerge. As if disease was not enough, food poisoning appeared. Tainted meat was, in desperation, consumed on many reserves and in many towns, with predictable results.

Still, the Canadian government adhered to an austerity-first policy and the notion of the “vanishing Indian” gained ground. Some Canadian critics of rationing and relief argued that supporting Indigenous peoples was throwing good money after bad: if the Indigenous population was doomed to disappear, what would be the point? In this respect, both the Liberals and the Conservatives in Ottawa were on the same page. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald took the view that relief to anyone who was not actually starving would create dependence rather than self-reliance. And yet, even in famine the Plains peoples were not being supported. One of the last big pushes to get bands onto reserves came in the spring of 1882 to clear all the lands south of the CPR route in Assiniboia (now southern Saskatchewan), especially the Cypress Hills, where thousands of peoples from different nations had gathered. As one historian frames this, every move made by Ottawa had cynicism at its heart: “Within a year, 5,000 people were expelled from the Cypress Hills. In doing so the Canadian government accomplished the ethnic cleansing of southwestern Saskatchewan of its indigenous population.”[4] In 1883, several Cree leaders petitioned Ottawa, clearly stating that they felt betrayed by Canada’s lacklustre commitment to the terms of the treaties:

Nothing but our dire poverty, our utter destitution during this severe winter, when ourselves, our wives and our children are smarting under the pangs of cold and hunger, with little or no help, and apparently less sympathy from those placed to watch over us, could have induced us to make this final attempt to have redress directly from headquarters. We say final because, if no attention is paid to our case we shall conclude that the treaty made with us six years ago was a meaningless matter of form and that the white man has indirectly doomed us to annihilation little by little . . . Shall we still be refused, and be compelled to adhere to the conclusion spoken of in the beginning of this letter, that the treaty is a farce enacted to kill us quietly, and if so, let us die at once?[5]

By 1884, the Nêhiyawak were prepared to speak as a single body under the leadership of Mistahimaskwa. In response, the Canadians—led by Lieutenant-Governor Edgar Dewdney and embodied in the newly-formed North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), both of which were based at Regina—began detaining Indigenous leaders as they attempted to travel to meetings, breaking up gatherings where legal resistance and court challenges were being discussed, and once again using rations to squeeze the Plains peoples into submission. The government also turned to the banning of Indigenous cultural practices. In 1884–85, movement was restricted by means of a “pass system,” and arrests were made of Indigenous diplomats visiting reserves other than their own. Disagreements arose between the Niitsitapi under Isapo-muxika (a.k.a. Crowfoot), the Hunkpapa Sioux (led by Ta-tanka I-yotank), the Nêhiyawak (whose spokesperson was Mistahimaskwa), and the Métis (led after 1884 by Louis Riel). The possibility of a united front emerging across the Plains was receding.[6]

As 1885 approached, relations between Indigenous peoples and Canadians in the West were at a low ebb. The worst of famine had passed in some quarters, but the trauma and the death toll were hardly going to be expunged overnight. Cree leaders like Piapot and Mistahimaskwa had watched for more than a decade as the Canadians neglected their treaty obligations and communities were purposely shattered and brought to heel.

The 1885 Rising

Protest letters gained no ground, and by March 1885 a loose coalition of Métis, settlers, and First Nations communities declared a provisional government. Less than a week later, some of their troops (led by Métis field general Gabriel Dumont and Assiwiyin) confronted a party of NWMP and members of a local militia drawn from settlers around Prince Albert. The battle at Duck Lake claimed nearly two dozen of the Canadian force, killed or injured; the coalition force lost only five, one of whom was Assiwiyin.

Indigenous unrest finally spilled over. A farming instructor was executed on the Mosquito Reserve, and the northern Nêhiyawak leader, Pitikwahanapiwiyin (a.k.a. Poundmaker, 1842–85), marched his followers and some Nakoda (a.k.a. Stoney) into Battleford on 30 March. Alarmed settlers abandoned the town, and the Indian agent was unwilling or unable to offer the Nêhiyawak-Nakoda protest group any food or resources. Looting of empty homes followed. At Frog Lake on 2 April, Mistahimaskwa’s Nêhiyawak broke with their moderate leader and attacked and killed nine settlers, including the Indian agent. Two weeks later, Fort Pitt was captured, although this time without bloodshed.

Less than twenty-four hours after Duck Lake, word reached Ottawa via the new telegraph technology that paralleled the Canadian Pacific Railway line. Macdonald called for volunteers for militia duty while local newspapers across Canada, from Fort William to Sydney, admonished settler males to step up and join local regiments sponsored by the newspapers themselves. (Under these circumstances, Canadian media accounts of the events of 1885 were bound to be slanted.) Two weeks later, about eight thousand soldiers (almost all of them inexperienced) were boarding trains and speeding west. The ability to do so had not been there in 1870; the failure of the Indigenous and/or Métis forces to cut the rail line or telegraph line suggests that their leaders did not appreciate the extent to which the world had changed since Red River in 1870.

The Canadian forces launched a two-pronged attack on the Nêhiyawak-Nakoda forces and the Métis provisional government headquarters at Batoche. Over three days, from the ninth through the twelfth of May, the Winnipeg Militia pounded away at the Métis position. Vastly outgunned, the Métis nevertheless held out until their ammunition was exhausted. As the Métis resistance failed, many of their troops and leaders fled. Three days after the battle, Riel surrendered. He was subsequently tried, convicted, and hanged in Regina.

The resistance to Canadian ambitions in the West was not over. Canadian troops performed less well against the Nêhiyawak: at Cut Knife Hill and Eagle Hills, and at Frenchman’s Butte and Loon Lake, Indigenous forces scored significant victories. However, the Canadians were wearing them down. Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa surrendered on 26 May and 2 July, respectively.

In the 1885 trials that followed in Battleford, the outcomes for the Indigenous leadership were particularly bad. Eight men—among them Kapapamahchakwew (a.k.a. Wandering Spirit) and the two Nakoda leaders (Itka and Man Without Blood)—were tried in October and condemned to hang. Some traditional Plains cultures believe that the soul is located in the neck, and so the idea of hanging was especially horrific. One of the condemned men unsuccessfully requested death by firing squad instead. A gallows large enough to hang eight men at once was built, and the mass—and public—execution took place on 27 November. It remains the largest public execution in the history of settler societies in what is now Canada. Evidence suggests that Indigenous children were brought from the Battleford Industrial School to watch. The fate of Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa was only slightly better. Along with One Arrow, they were each sentenced to three years at Manitoba’s Stony Mountain Penitentiary—itself an expression of growing settler society power on the Prairies. All three leaders were badly reduced in health by the experience and were released ahead of schedule; they all died soon thereafter as a result of their incarceration.

In the aftermath of the trials, executions, and imprisonments, many Nêhiyawak and Nakoda fled to the United States. While the story of Ta-tanka I-yotank and the Sioux flight into Canada is relatively well known, the fact that a couple of hundred Indigenous people from the Canadian Plains thought themselves safer south of the Medicine Line is not.[7]

Ironically, the Sioux who remained north of the border fared the best in these years. They brought their farming skills (honed for more than 50 years) to their existing settlement hubs in Canada. They were not covered by numbered treaties and, as a result, fell between the administrative cracks. They didn’t face the scrutiny of Indian agents and could largely ignore the pass system. Although they weren’t eligible for government relief, that was rarely forthcoming anyways. They were thus able to get on with adjusting to the new paradigm without wilful mismanagement by the Canadians. How serious was this distinction? Very. Of the Plains people in the 1880s, only the Sioux escaped the tuberculosis epidemics, and they did so likely because they were better fed, more self-sufficient, and not economically destabilized.

Conclusion

The events of 1885 foreshadow changes that were to befall Indigenous communities across the country. Settler society would introduce more stringent laws and regulations and would increasingly monitor Indigenous behaviour and punish transgressions. 1885 gave elements in Canadian society license to “manage” Indigenous cultures, which translated into assimilative policies and what has come to be regarded as cultural genocide. The century and more of policies associated with Canadian settler colonialism are the subject of the next section.

Additional Resources

The following resources may supplement your understanding of the topics addressed in this chapter:

Daschuk, James. Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013. See esp. pp. 79–180.

Ferguson, R. Brian, and Neil L. Whitehead. “The Violent Edge of Empire.” In War in the Tribal Zone: Expanding States and Indigenous Warfare, edited by R. Brian Ferguson and Neil L. Whitehead, 1–30. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 1992.

Gaudry, Adam. “The Métis-ization of Canada: The Process of Claiming Louis Riel, Metissage, and the Metis People as Canada’s Mythical Origin.” Aboriginal Policy Studies 2, no. 2 (2013): 64–87.

Graham, Sean. “History Slam Episode Sixty-Three: Metis and the Medicine Line.” Produced by Active History. History Slam. June 25, 2015. Podcast, MP3 audio, 51:07. http://activehistory.ca/2015/06/history-slam-episode-sixty-three-metis-and-the-medicine-line/

Hogue, Michel. “Podcast: Setting the Plains on Fire: How Indigenous Geo-Politics and the U.S.-Dakota War shaped Canada’s Westward Expansion.” Produced by Active History. History Chats. May 12, 2018. Podcast, MP3 audio, 26:30. http://activehistory.ca/2018/05/podcast-setting-the-plains-on-fire-how-indigenous-geo-politics-and-the-u-s-dakota-war-shaped-canadas-westward-expansion/

Hoy, Benjamin. “Little Bear’s Cree and Canada’s Uncomfortable History of Refugee Creation.” Active History, September 9, 2015. http://activehistory.ca/2015/09/little-bears-cree-and-canadas-uncomfortable-history-of-refugee-creation/

Innes, Robert Alexander. “Historians and Indigenous Genocide in Saskatchewan.” Shekon Neechie: An Indigenous History Site, 21 June 21, 2018. https://shekonneechie.ca/2018/06/21/historians-and-indigenous-genocide-in-saskatchewan/

Many Guns, Cecile, and Annie Buffalo. “Interview with Mrs. Cecile Many Guns Grassy Water) and Mrs. Annie Buffalo (Bear Child).” By Dila Provost and Albert Yellowhorn Sr. University of Regina, oURspace, 1973. http://ourspace.uregina.ca/handle/10294/586

McCoy, Ted. “Legal Ideology in the Aftermath of Rebellion: The Convicted First Nations Participants, 1885.” Histoire Sociale/Social History 42, no. 83 (Mai-May 2009): 175–201.

Milloy, John. “‘Our Country’: The Significance of the Buffalo Resource for a Plains Cree Sense of Territory.” In Aboriginal Resource Use in Canada: Historical and Legal Aspects, edited by Kerry Abel and Jean Friesen, 51–70. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1991.

Read, Geoff, and Todd Webb. “‘The Catholic Mahdi of the North West’: Louis Riel and the Metis Resistance in Transatlantic and Imperial Context.” Canadian Historical Review 93, no. 2 (June 2012): 171–95.

Smith, Keith. Liberalism, Surveillance, and Resistance: Indigenous Communities in Western Canada, 1877-1927. Edmonton: University of Athabasca Press, 2009.

Stark, Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik. “Criminal Empire: The Making of the Savage in a Lawless Land.” Theory and Event 19, no. 4 (2016).

Stonechild, A. Blair. “The Indian View of the 1885 Uprising.” In 1885 and After: Native Society in Transition, edited by Laurie Barron and James B. Waldrum, 155–70. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1986.

Waiser, Bill. “They Have Suffered the Most: First Nations and the Aftermath of the 1885 North-West Rebellion.” In Roots of Entanglement: Essays in the History of Native-newcomer Relations, edited by Myra Rutherdale, Kerry Abel, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, 233–58. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

- The material in this chapter derives from John Douglas Belshaw, Canadian History: Post-Confederation (Vancouver: BCcampus, 2016), sections 2.5–2.8. The material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- This section derives and has been adapted from by John Douglas Belshaw, “2.6 Canada and the First Nations of the West,” Canadian History: Post-Confederation (Victoria: BCcampus, 2015), and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- John Milloy, The Plains Cree: Trade, Diplomacy and War, 1790 to 1870 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1988), 120. ↵

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 123. ↵

- Bobtail et al. to John A. Macdonald, January 7, 1883, quoted in Jennifer Reid, Louis Riel and the Creation of Modern Canada: Mythic Discourse and the Postcolonial State (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 15. ↵

- J. R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens, 170–5. ↵

- Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser, Loyal till Death: Indians and the North-West Rebellion (Calgary: Fifth House Publishers, 1997), 222-5. ↵